In the course of putting together one of my recent posts (The Missing Outage) I came across another very interesting government publication from 1888 bearing the rather ponderous title of Internal Revenue Manual Compiled at the Direction of the Commissioner of Internal Revenue from the Laws and Regulations Now in Force, for the Information and Guidance of Internal Revenue Officers and Agents, September 1, 1888 [1]. In the interest of brevity, I’m going to henceforth refer to this just as the 1888 Manual.

The 1888 Manual was intended as a guide for employees of the Internal Revenue Service (‘Officers and Agents’) working out in the field, typically on-site at one or more distilleries to oversee day-to-day operations, ensure compliance with the law, and keep required records. It describes a number of specific roles that needed to be filled, e.g. Shop-Keeper and Gauger, along with a practical guide to enforcing various federal statues as part of performing those roles. It therefore goes into the nitty-gritty implementation details that can only be implied by a piece of legislation. For example, the 1888 Manual is where the Shop-Keeper, the person responsible for overseeing the all the day-to-day operations at a distillery, would find a comprehensive list of buildings and rooms at the distillery that must be secured with a government controlled lock, for which only they would hold keys, e.g. the doors to a bonded warehouse [2].

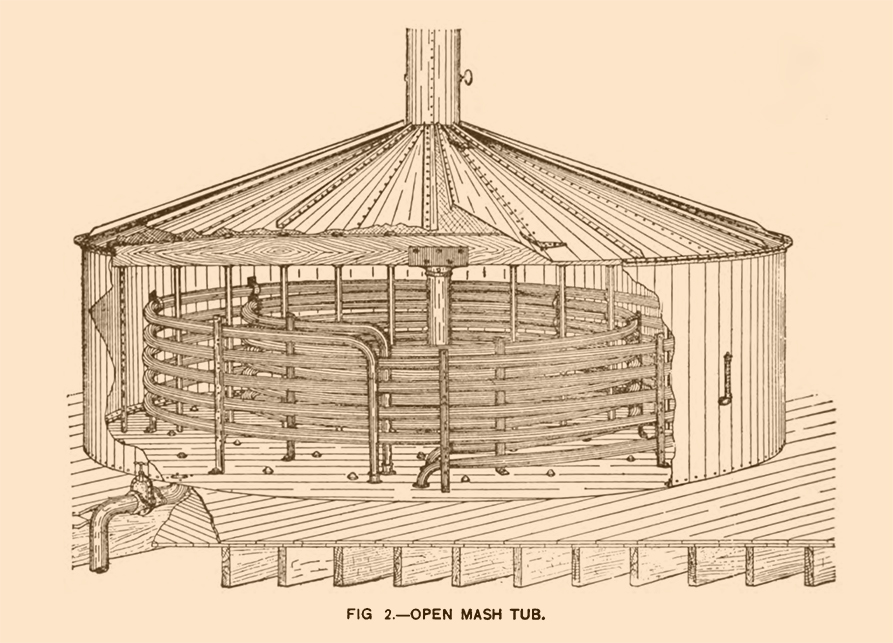

But what really caught my attention in the 1888 Manual was the section regarding the oversight of mashing and fermentation. The government really got ‘right into the grills’ of distilleries at this time about how these steps were to be performed, how large the mash tubs could be, the ratios of water to grain used, how often they were cleaned, and how much time fermentation was expected to take. I think this was all part of keeping tabs on how much spirit the distillery was capable of producing per unit time and therefore how much tax they’d likely owe. (With distilling, sooner or later, everything always seems to come down to taxes.)

The really big surprise is that in 1888 the federal government only described a single technique for sour mashing, what can also be referred to as ‘old fashioned sour mash’ which meant depending on wild yeast to start fermentation. Here’s the relevant text:

“Sour-mash distilleries may be briefly described as those in which no fermenting agent other than spent beer or slop is used, but the grain is mixed with the slop directly from the still and allowed to remain twenty-four hours, at the end of which period the mash becomes hard and sour.”

The implication was that wild yeasts, living within the room used for mashing, was enough to get fermentation started. It also implies that any technique which involved adding yeast would be considered sweet mashing.

A brief point of order

I think it would be useful to note that the federal government has never defined a standard for sour or sweet mashing that a whiskey using either term on the label would need to conform with. The descriptions appearing in a publication like the 1888 Manual were probably provided simply as informative outlines so IRS employees working at a distillery would have an idea of how these methods differed from each other, i.e. they didn’t need to be entirely accurate. The only thing a Shop-keeper probably needed to know was how to differentiate between types of fermentation in order to enforce regulations regarding frequency of mash tub reuse.

Where there was one, now there are three

Twenty-four years later, in 1912, the federal government publishes another document called Bulletin Relative to Production of Distilled Spirits, Published by the Bureau of Internal Revenue for the Information of its Officers. I’m just going to call this one the 1912 Bulletin. This might or might not be a descendant of the 1888 Manual, though if it is, it’s been greatly slimmed down. There’s also a few very striking differences in the descriptions of mashing and fermentation techniques.

There is no longer an explicit discussion of sweet mashing though it seems that it’s still recognized as a fermentation technique. I might assume this means the distilling industry was moving away from its use by this time. Perhaps more significantly, there are now three distinct types of sour mashing described. I will outline the differences using the headings that appeared in 1912 Bulletin:

“First method, no yeasting used” This appears to be the technique closest to what’s outlined in the 1888 Manual. The part where spent beer or slop (AKA backset) would be added to the mash is strangely absent. Despite this omission, the 1912 Bulletin states “In the early days of the industry this was the general method employed.” Seem like something was lost and as I suggested already, the aim might not have been perfect accuracy.

“Second method, yeasting back, or the old-sour mash process” It’s a little unclear but it seems that this technique starts with some jug yeast to get things going. Once started, older yeast from the previous days ferment can be used in each new days ferment. The description also seems to suggest that eventually there’s spoilage due to bacterial contamination and then you’d need to start over from scratch. (N.B. I do not know why they call this ‘the old-sour mash process’ and not the first technique.)

“Third method, yeast mash.” This is possibly what would have been called ‘sweet mashing’ in 1888 however it allows for the growth of so-called ‘lacto acid bacteria’ (LAB) in the mash (by letting it sit for 24 hours at a temperature of 124° F) so as ‘sour’ the beer. The mash once so soured may just be cooled or it may be heated to kill the bacteria before pitching with yeast.

And then back to one (or is it two)?

You’ll notice that none of these techniques corresponds with what people today are taught about sour mashing, to wit: that fresh yeast is used along with some amount of spent beer or slop (AKA backset) to provide acidity during fermentation. It’s a reasonable assumption that techniques continued to evolve after 1912 (and after Prohibition) and that ‘yeast + backset’ sour mashing became the norm since then. [3] I am hoping to find a more recent version of these manuals (or at least their modern equivalents) so I might confirm that. It’s also possible I won’t find any thing because as the government eliminated on-site monitoring of the whiskey production process, it may have simply stopped bothering to document at this level of detail. I’ll keep looking however and if I find something, I’ll write an update to this post.

Addendum

I am hardly the first person to pull on this particular thread, though I think my angle is new. In acknowledgement of work done by others, I’d like to provide a list of web articles for folks interested in learning more on this topic:

The Different Meaning Of Sour Mash In the 1800s

Bourbon Sour Mash: From E.H. Taylor to Dr. James Crow

Sour Mash: All Roads Lead to Crow?

—

NOTES:

[1] The federal government of that time seemed to love lengthy titles like this. It also loved changing the titles of documents, even if just slightly, with each subsequent revision. This is one of the things that makes it hard to find updates.

[2] They’d also find such arcana as the colors that pipes carrying various liquids around the distillery should be painted.

[3] Apparently the technique of inoculating the mash with LAB + yeast, completely omitting the use of backset, is also employed today. However, I’ve never heard a distillery state they use this technique when they talk about their mashing process. If I hear different, I will update this post.