In 1936, shortly after the ratification of the 21st amendment and the end of Prohibition, the federal government undertook a long overdue project to organize and harmonize years and years of rules and regulations that resulted from all of the laws it had passed since the Constitution itself had been approved. The fruit of this effort was the Code of Federal Regulations, or CFR. It was in effect an outline into which the rules and regulations for pretty much everything the federal government had oversight over could be organized. Most importantly, with that organization in place, it would be possible to know, more or less, where to look for the rules and regulations.

By current standards of legislative effort and efficiency, the CFR was a miracle document, with many sections, formally referred to as ‘Titles,’ completed two years later in 1938. One of these, was Title 27, covering rules and regulations pertaining to alcohol, tobacco and firearms (guns). It is in the 5th part of Title 27, entitled ‘Labeling and Advertising of Distilled Spirits’ where we can find all of the various standards of identity for spirits including most famously the ones for Bourbon and rye whiskey. Colloquially this section is referred to as ’27 CFR 5.’

There is sadly no record today of which ‘authorities’ were asked to contribute to the effort of writing 27 CFR 5. Of course, about some members of this group we can make educated guesses. For example, the requirement set forth in 27 CFR 5.22(1)(i) that Bourbon, rye, wheat, and malt whiskey be stored in ‘charred new oak containers’ has no legal precedent prior to Prohibition. But just by writing it down here, it suddenly becomes law, written apparently out of whole cloth. Granted, this might have represented ‘best industry practice’ before 1920 but, still, prior to this point the federal government had been neutral on the subject. But as the old expression goes: ‘follow the money’ and the direct beneficiaries of this new requirement would be the timber and cooperage industries. So I think it’s reasonable to assume interests of both these groups were well represented in the writing effort.

But the particular mystery I wanted to explore has to do with the very odd definition for ‘straight’ that appeared in 27 CFR 5, seemingly for the first time anywhere. Here’s that definition:

“Whiskies conforming to the standards prescribed in paragraphs (b)(1)(i) and (ii) of this section, which have been stored in the type of oak containers prescribed, for a period of 2 years or more shall be further designated as ‘straight’; for example, ‘straight bourbon whisky’, ‘straight corn whisky’, et al.”

What makes this odd is that prior to Prohibition, in documents like the Taft Decision in 1906 and then the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1909 [1], the term ‘straight’ only concerned itself with the manner in which the whiskey in question had been made, e.g. if it had been made solely from distilled grain and aged in wood, without any additives other than water, then it was ‘straight.’ There is no example usage I’ve been able to locate which makes any requirement that a straight whiskey also be aged for some minimum amount of time, let alone two years.

Moreover, the preceding sections of the standard, paragraphs (b)(1)(i) and (ii)), really do all the work (and then some) that the old definition of straight used to do. That’s where we read about minimum grain type requirements, maximum proof coming off the still, maximum entry proof going into barrels, and allowable types of barrels. But now there’s a ‘further’ requirement that to use the original term, the whiskey also needs to be aged for at least two years. As I said: it’s an odd addition, without explanation.

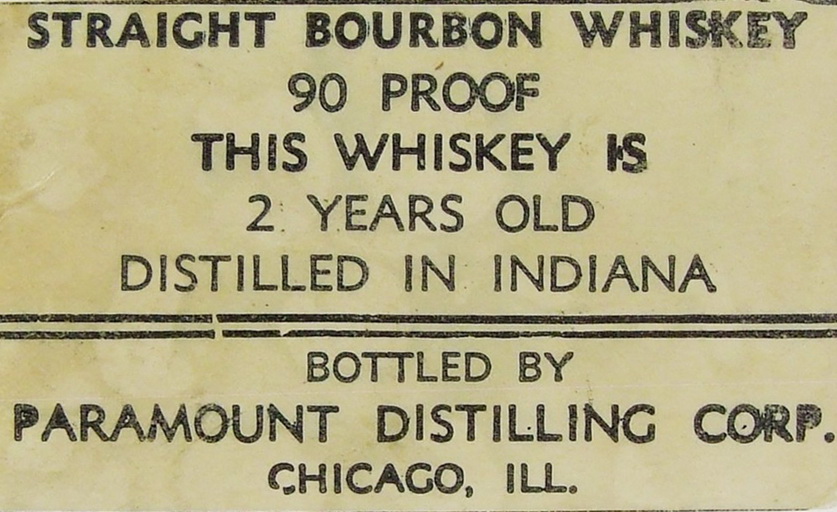

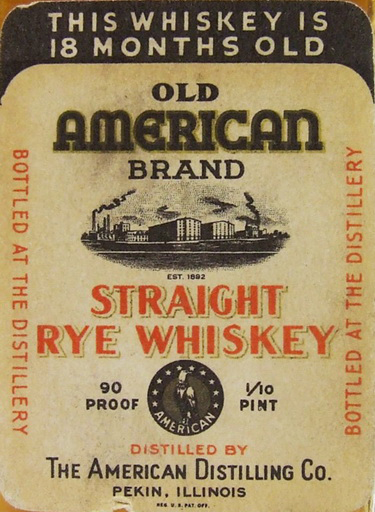

Unfortunately, I don’t think we’re ever going to be able to determine what was on the minds of the people who made labeling as a straight contingent on the length of time the whiskey was aged for. It’s not as obvious as the link between ‘charred new oak containers’ and barrel makers. We do know it was important enough to the authors that they provided for a grace period between 1936 and 1938 which allowed whiskies younger than two years to be labeled as straight [2]. I have actually wondered if this part of 27 CFR 5 was a) just poorly written at the time and b) was intended to have been removed after the distilling industry, just re-starting after Prohibition, had acclimated itself to the new standards, i.e. there wouldn’t have been a two year minimum requirement for straight whiskies made after 1938. [3]

—

NOTES:

[1] – More specifically, it was Food Inspection Decision (FID) 55 which implemented this under the purview of the Pure Food and Drug Act. The Act itself just provided a framework for regulation.

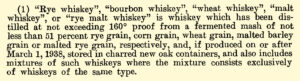

[2] The very first version of 27 CFR 5 published in 1938, included a definition for straight that read quite differently from the one you find today, which I already quoted above. Here’s what you would have read in 1938:

“(2) ‘Straight whiskey’ is an alcoholic distillate from a fermented mash of grain distilled at not exceeding 160° proof and withdrawn from the cistern room of the distillery at not more than 110° and not less than 80° proof, whether or not such proof is further reduced prior to bottling to not less than 80° proof, and is (i) Aged for not less than 12 calendar months if bottled on or after July 1, 1936, and before July 1, 1937; or (ii) Aged for not less than 18 calendar months if bottled on or after July 1, 1937, and before July 1, 1938; or (iii) Aged for not less than 24 calendar months if bottled on or after July 1, 1938”

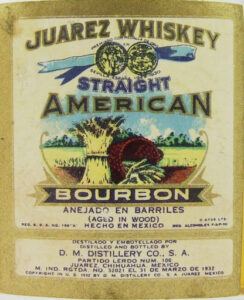

And, in fact, here’s an example of an 18 month old straight from that time:

Also notice that a lot of the requirements in the 1938 version wind up being shifted to the previous paragraphs after the revision. All that would have been left after that change would have been the two year aging requirement, making the entire definition of straight now rest upon that one entirely new criteria.

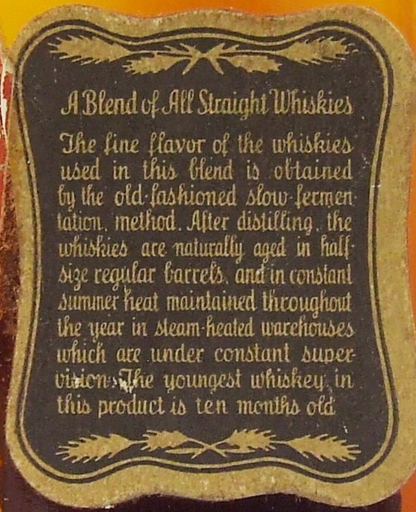

Finally, and a bit of an addendum, here’s the back label for a ‘Blend of Straights’ released by Old Oscar Pepper (Frankfort Distilleries Incorporated) from 1934. It states, at the bottom of the label, the youngest whiskey in the blend is 10 months old. This would obviously not pass muster after 1938 when 27 CFR 5 was published. This pretty clearly shows the old definition of straight was still being used by the distillery industry prior to this. I’m not sure there’s any reason to think it would be changed either.

[3] One more thought on this matter, which crossed my mind a few hours after posting. I have an adage that when something seems inexplicable with regards to the beverage alcohol business, the most probable explanation is ‘taxes.’ (Don’t know why this didn’t occur to me sooner.) So perhaps there’s some taxation reason why the two year minimum aging requirement was added in 1938. I haven’t connected the dots yet but maybe some more sleuthing will reveal it.

Pingback: In Praise of American White Oak – In the American Grain

Pingback: How Straight Got Its Modern Meaning – In the American Grain