We should try getting them right!

A week or so ago I attended an ‘experience’ at one of the many distilleries in Kentucky now offering tours and tastings. Like many similar offerings, it included a recap of various important milestones in American whiskey history. And as happens all too often, one or more of these milestones was attributed to the wrong event and date. I guess this isn’t the biggest deal but when those of us who represent the distilling industry are asked to tell the story of Bourbon to the general public I think it’s important to get these details right. So below you’ll find what I hope can serve as a clarifying guide to those milestones for everyone.

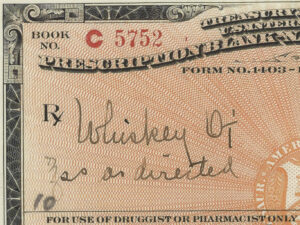

1909: ‘The Taft Decision’

Neither distillers nor rectifiers were happy with the definition of whiskey that was put forth as part of the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906 (AKA Food Inspection Decision 65). In an attempt to mollify both interest groups (as well as showing off his skills as a jurist) then President William H. Taft took it upon himself to hear arguments from representatives of both parties and come up with a set of definitions that everyone might be willing to live with. The so-called Taft Decision was published in January 1909.

What the Taft Decision DID: It created a clear definition for ‘straight whiskey,’ which could only be made from fermented grains, distilled and then aged in a barrel and allowed rectifiers to keep using the term ‘whiskey’ for their products (based on historical precedent) without adding the qualifier ‘imitation’ or ‘compound’ to the label.

What the Taft Decision DID NOT DO: It did not define ‘Bourbon,’ a term which Taft used but only to say that it, along with the term ‘rye,’ could be placed on a barrel of straight whiskey if the distiller wanted to and if warranted by the composition of the grains used to make the it. And that’s as far as he goes—on the matter of grain composition, i.e. mash bills, he has nothing to say.

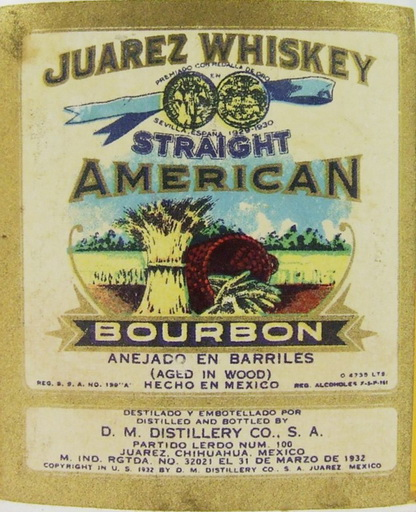

1938: 27 CFR 5 Labeling and Advertising of Distilled Spirits

I recently wrote about this document, which was part of a huge undertaking by the federal government to (finally) organize and structure all the regulations and requirements that had been created since the constitution was ratified.

What 27 CFR 5 DID: Created a clear definition for several types of American whiskey, including Bourbon and rye, based on the composition of the mash bills, the proof of the resulting spirit coming off the still, the entry proof of the spirit when put into the barrel, as well as the composition of the barrel itself. It also defined a set of rules for labeling these spirits.

What 27 CFR 5 DID NOT DO: It did not provide for any kind of special trade protection for the terms Bourbon or rye whiskey. This meant these terms could appear on the label of a whiskey made anywhere in the world so long as it conformed to the corresponding standard of identity (if the producer was honest).

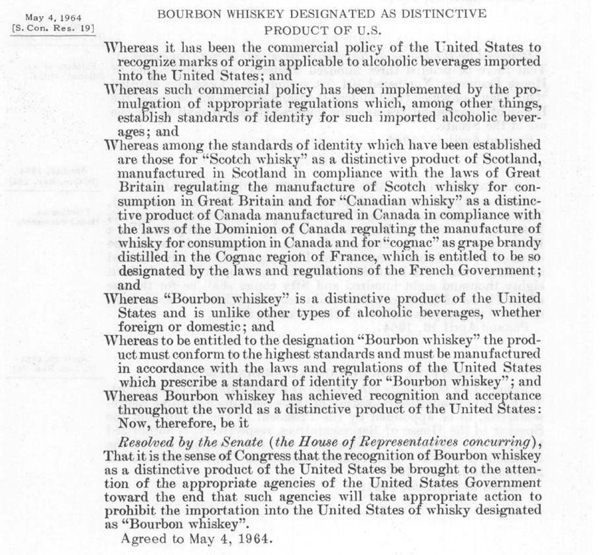

1964: Senate Concurrent Resolution 64

This is the result of lobbying work done by the so-called ‘Bourbon Institute’ to provide special trade protection for the use of the term ‘Bourbon’ much as the name ‘Champagne’ or ‘Scotch’ were protected for products made in France and Scotland, respectively. Most all U.S. trading partners abide by agreements like this.

What Resolution 64 DID: Prevent someone from labeling a product made outside of the United States as ‘Bourbon’ but which otherwise conforms to the standard of identity in 27 CFR 5. And by extension, it makes selling a product so labeled illegal in the United States as well.

What Resolution 64 DID NOT DO: It did not ‘define’ Bourbon other than to say that a product so labeled can only be made in the United States. And it does not provide any special protection for the use of the term ‘rye’ which can have different meanings in different countries.

![Read more about the article A Pilgrim in Shively [Part II]](https://americangrain.stream/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/IMG_2819_FourRoses_Warehouse01-300x225.jpg)