Preamble

Whiskey nerds often like to go on about how easy it would have been ‘back in day’ to bag what today would be considered unicorn finds, paying then retail prices for bottles that now go for thousands of dollars. It’s a fun (if pointless) exercise, but it did get me thinking: if I had been interested in American whiskey back in a decade like the 1990s, exactly how would I have known where to begin? Without the hindsight I have today, how would I have figured out what I should have been drinking (and hoarding), short of trial and error?

Internet, anyone?

There was of course an internet and the beginnings of the world wide web by the mid-1990s. But anyone used to what we take for granted today would have found it very very primitive: no social media, no youtube, no podcasts, no Fred Minnick. There were some early search engines but google wouldn’t exist until the end of the decade. Instead there was a thing known as a ‘webring’ where people with subject-matter focused websites would agree to link to each other. (Required exchanging emails and possibly a moderator.) However, two of the most seminal Bourbon websites (more like BBSes really) had not yet been launched. The first would be straightbourbon.com in 1997 followed by bourbonenthusiast.com in 2004. And it would take several years of user contributions before these sites would really turn into useful resources. So the 90’s internet wouldn’t have been of much help.

OK, then what about books?

Today there’s an abundance of books to choose from, starting with Mike Veach’s seminal work Kentucky Bourbon Whiskey: An American Heritage (published in 2013) through Clay Riesen’s American Rye: A Guide to the Nation’s Original Spirit (published in 2022). A search for “American whiskey” on Amazon’s book section returns over 7000 matches. It’s really incredible when you think about it. But in 1994, the pickings would have been pretty slim—far slimmer than the choice bottles sitting on liquor store shelves wait for me to discover them.

To get an idea of what books might have been available to the 1990s version of me I used the Library of Congress (LoC) on-line catalog and keyword search to find what had been published between 1933 and 2000. That search returned a little over 100 ‘hits’ which I then sifted through by hand, eliminating books on subjects like alcohol abuse or Scotch (i.e. the other ‘whisky’). There were also a couple of promotional books written by the distilleries themselves, though locating these might have been challenging. In the end, I found only six relevant titles.

There were three histories:

- The Social History of Bourbon by Gerald Carson, 1963

- Kentucky Bourbon: The Early Years of Whiskeymaking by Henry G. Crowgey, 1971

- Whiskey: an American Pictorial History, by Oscar Getz, 1978

These are three nice books, still in print today, all well regarded for their historical importance. Someone looking to know more about American whiskey history even today would be well served by seeking them out. However none of these would have helped 1990s me decide what to pick up at the liquor store.

The last three, fortunately, were the real pay dirt:

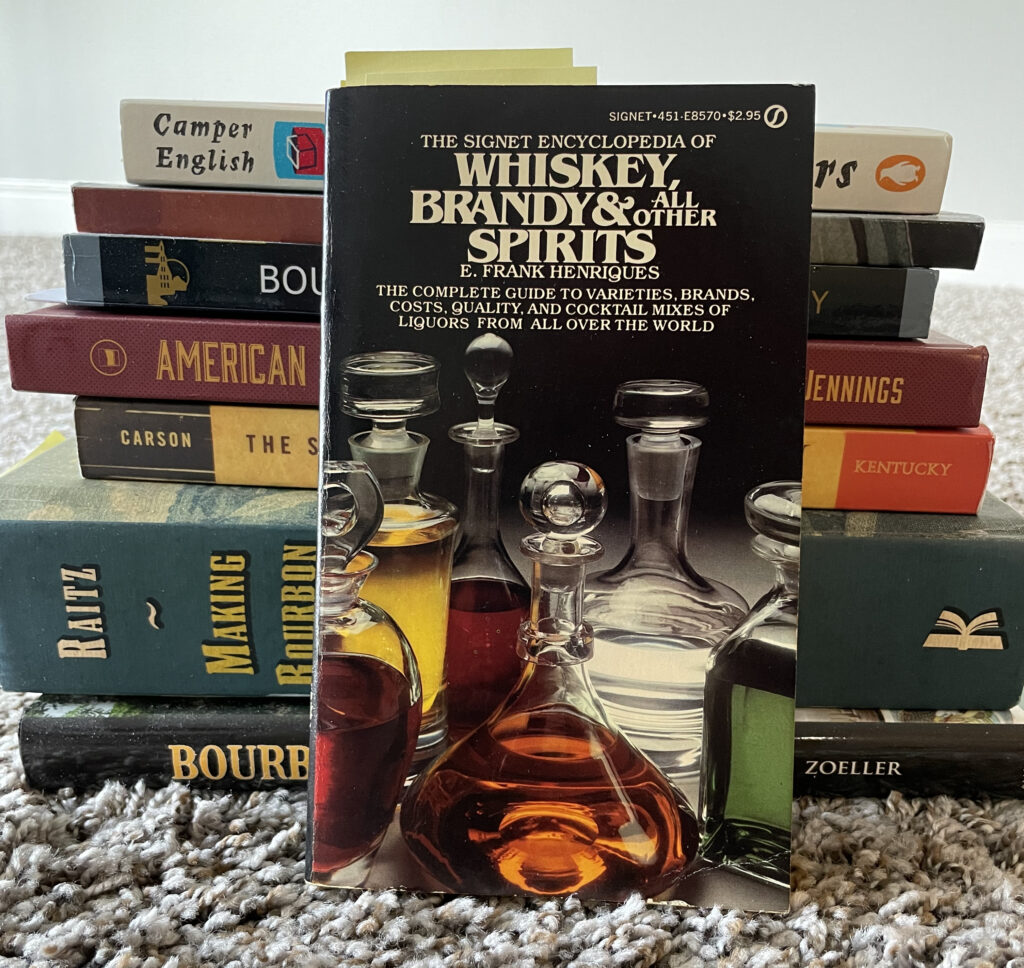

- The Signet Encyclopedia of Whiskey, Brandy, and All Other Spirits, by E. Frank Henriques, published 1979

- World Guide to Whisky : Scotch, Irish, Canadian, Bourbon, Tennessee Sour Mash, and the Whiskies of Japan, by Michael Jackson, first published 1988

- The Book of Bourbon and Other Fine American Whiskeys, by Gary Regan and Mardee Haidin Regan, published in 1995

Three guide books published over almost two decades didn’t seem like a lot to go on. But remember: this was before today’s Bourbon explosion. The choices I’d have found on contemporary liquor shelves had probably remained fairly constant…for at least 30 years. I suspected even the oldest book on that list would have provided a starting point. So that’s where I’ll begin.

The Signet Encyclopedia of Whiskey, Brandy, and All Other Spirits, 1979

Say the word ‘encyclopedia’ to someone old enough to actually remember when these were a thing is to evoke the image of a shelf filled with thick leather bound books. There would have been at least 26 of these in the set, one per letter of the alphabet, but frequently more if we’re talking about something really massive like the Encyclopedia Britannica [1]. The Britannica was of course the gold standard for such reference works and usually the shelf its volumes lived on would have been in a library. (They were expensive!)

I’m providing this context simply because The Signet Encyclopedia of Whiskey, Brandy, and All Other Spirits was nothing like that. It was in fact a paperback book that retailed for all of $2.95 (USD). The page count was 243, including the index. A modest offering, really. But if you were looking to learn as much as possible about American whiskey in the late 1970s, this would have pretty much been your only option.

Let’s first look at the fides of the author, E. Frank Henriques. According to the short biographical sketch at the back of the book, Henriques, who passed away in 2002 at the age of 82, was an Episcopal priest, born in San Francisco, and lived most of this life in the Mother Lode country in northern California where he was pastor of the Trinity Church. His only other written work was The Signet Encyclopedia of Wine, another paperback, published in 1975.

Of his expertise in the subject at hand, Henriques states that it:

“…comes not from extensive ‘lab work’ but from probing study, diligent note-keeping, and a ‘fond regard’ for his subject matter.”

In other words, he makes it sound like he’d have fit in perfectly in today’s landscape of bloggers, instagramers, and self-educated writers. I would say he was just very early to the table.

Being an encyclopedia, it presents its subjects as a series of short topical blurbs/articles arranged in alphabetical order. This made it was a little hard to figure out how to approach an evaluation of its merits. Also remember that this book covers quite a bit more than just Bourbon, so I wasn’t inclined, at least initially, to make a cover-to-cover reading [2].

Ultimately, I decided that I’d start by reading the entry for Bourbon first, followed by entries for individual brands and distilleries [3]. It was also one of the lengthiest entries.

Immediately, I was struck by Henriques’ writing style: it’s informative but often becomes overly chatty or colloquial, like he’s speaking to a friend. For example, the Bourbon entry provides a relatively good summation of the rules for Bottled-in-Bond, but then concludes:

“These are the most bourbonish whiskies you can buy. Be advised: Buy the most economical! There is no appreciable difference in taste between them.” [4]

The statement that he found no appreciable difference between these was somewhat startling. (His list of of recommendations, along with pricing, is below.) Even in the ‘dark days’ of the 1970s distilleries were making and selling a variety of Bourbons of differing ages and qualities, from bottom to top shelf. So its hard to imagine someone intent on writing a “probing study” would have found no better criterion for selection than price. In Henriques’ defense, however, one might consider that in the 1970s price might have been a more overriding consideration than the kind of sensory qualities we place value on today. He may simply have been playing to his audience in this regard.

Henriques’ list of recommended Bottled-in-Bond Bourbons, listed in order of price from lowest to highest:

N.B. The prices are going to be shocking!

- Haller’s County Fair, $4.68

- Old Log Cabin, $5.55

- Hiram Walker Private Cellar, 6 years, $5.60

- Old Heaven Hill, 4 years, $5.87

- Barton’s Ancient Bond, 8 years, $5.89

- Fleischmann’s, $5.89

- Spring River, $5.89

- Old Hickory, 6 to 7 years, $6.07

- J.W. Dant, $6.25

- Old Crow, $6.25

- Old Kentucky Tavern, 8 years, $6.77

- Old Forester, 6 years, $7.55

- Old Fitzgerald, 6 years, $7.55

- I.W. Harper, $8.22

- Old Grand Dad, $8.22

The entries for individual brands would continue to reflect this writing pattern. After giving a bit of history, Henriques offers only rather superficial distinctions (‘smooth’ ‘light’ ‘heavy’ ‘good’ ‘fine’ ‘mild’) with the net effect of flattening any other differences between brands out. And again, price seems to remain his primary fixation, never sensory delight.

In the end, I had to go through all the brand entries (almost 100) to find anything he considered better than average and/or possibly worth the money. There were really only three.

Of Old Fitzgerald he says “Bourbon fanciers have been fervent of their praise for it.” Of Old Grand Dad: “Nobody disputes the excellence of this straight bourbon whiskey” but he then goes right on to note that in some “well-known tasting” it had been judged merely “acceptable” and complains about the price. He saves his highest praise however for Old Taylor: “…many experts agree that [it] is exceptional whiskey even among premium bourbons.” [5]

Henriques also reveals an odd disenchantment with the opinions of so-called ‘expert tasters,’ though he never indicates who these people are and where they are sharing their opinions. Distinctions between whiskies are either only detectable by these experts (i.e. don’t waste your money) or these same experts are unable to detect claimed differences (i.e. if the experts can’t tell the difference, neither will you). Henriques is clearly trying to paint himself as a kind of ‘every man’ whom the neophyte should find to be relatable. But by buying his book, are we not acknowledging the author himself as an expert? (Shrug.) Regardless, the overall effect is, once again, to leave one feeling there’s not many distinctions to be made among different offerings apart from price. No magic to be found on the shelves.

Finally, I was surprised to find two notable brand omissions.

The first was W.L. Weller. It gets only a mention in the entry for Old Fitzgerald as another brand of Stitzel-Weller. Though, he also notes that there’s a 107 proof version of the Weller, declaring: “aargh, proceed with caution—at $11.50 for a fifth.” And there were certainly other Weller bottlings that would have been even more expensive. So given his penchant to ‘go cheap’ he might not have felt Weller was worthy of inclusion.

The second missing brand was Maker’s Mark. Maker’s had been around since the 1960s but it remained a very small distillery until the 1980s, when it was sold to Hiram Walker. So it’s possible it didn’t yet have distribution in all 50 states. Henriques may have simply never encountered it in the wild. On the other hand, Maker’s, which built part of its reputation around being more expensive than other Bourbons, might not have passed Henriques’ value-for-the-buck ‘sniff test.’

Too little, too early?

Had 1990s me had only The Signet Encyclopedia of Whiskey, Brandy, and All Other Spirits to serve as my buying guide, I might not have turned out to be much of a Bourbon geek. Looking at it through modern eyes, it just doesn’t provide the sort of enticement that would to bring a n00b into the fold.

In all fairness, however, this is a small book covering far more than just Bourbon, written at a time when predominant tastes still ran to spirits of a clearer and lighter nature. Henriques had a lot of ground to cover and the entries on the cocktails and various liqueurs (many now out of production) appear to be much more detailed. But as a guide to someone in the 1990s wanting to navigate their the shelves of their local liquor stores looking for Bourbon, this book leaves a lot to be desired.

Next up: World Guide to Whisky: Scotch, Irish, Canadian, Bourbon, Tennessee Sour Mash, and the Whiskies of Japan, 1988

—

Notes:

[1] The 15th edition, published in 1988, spanned 32 volumes.

[2] There’s actually a lot of other fun stuff in here, especially if you’re a cocktail geek with interest in drinks being served in the 1970s and old/defunct ingredients. (Peanut Lolita, anyone?) There are close to 100 cocktails listed in the index. This leads me to believe that Henriques was far more more interested in this kind of drinking than he was in individual spirits.

[3] – There are no entries on general topics like mashing, fermentation, distilling, or barrels, things we’d expect in a modern book on whiskey. The one exception is an entry on congeners, of all things. It’s short but surprisingly detailed.

[4] At the other extreme, when discussing light whiskey, he says “…light whiskey is a bourbonless bourbon” which I found quite amusing.

[5] – Henriques’ greatest praises seem to be reserved for products that have ‘Old’ in their name, making me wonder if he’s more influenced by marketing that he realizes.