A short preamble…

Like many history investigators, the internet is one of my primary research tools, more specifically search engines which help me locate a variety of different source materials. Ideally I’m hoping to find primary sources such as historical documents and government records. But every so often I come across some new means of locating content. Recently that took the form of the Library of Congress’ on-line catalog. [1] I’d certainly found lots of important documents in the Library of Congress (LoC) collections just using google, but it never occurred to me to use their catalog directly. But I digress…

What led me to the LoC catalog in the first place was a need to do some sleuthing for another piece I’m writing about a Bourbon book written back in the 1990s. Catalogs like the one the LoC provides allow users to specify much more sophisticated search parameters/constraints than general internet search engines. This is mostly because libraries typically provide more complete metadata tags for items in their collections. In my case, I was looking for something pretty specific: non-fiction books tagged with the subject ‘whiskey’ published between 1933 and 2000. The search returned a little over 100 ‘hits’ which then needed to be manually reviewed [2].

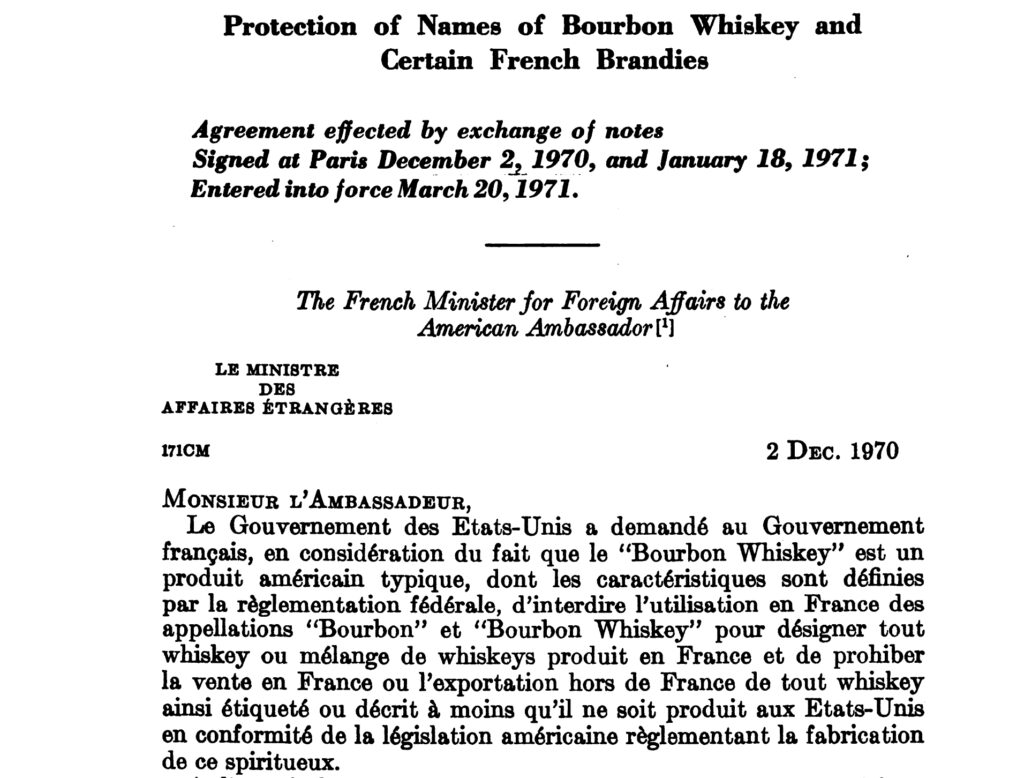

Buried in that list was something I hadn’t been looking for but which immediately got my attention. It was a collection of trade treaties and agreements entered into between the United States and other nations in 1970 and 1971, published by the Department of State in 1972 [3]. One of the agreements was between the United States and France, titled Protection of names of Bourbon whiskey and certain French brandies [4]. By signing it, the French government agreed that Bourbon was a distinctive product of the United States and further that it can only be made there and in accordance with its defined standard of identity. In other words, in 1971 France agreed to abide by another document that had been approved and published back in 1964 known as Concurrent Resolution 64.

Concurrent Resolution 64 in Effect

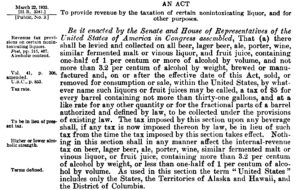

I already discussed Concurrent Resolution 64 a few months back when I wrote about Three Important Dates in American Whiskey History. Enacted by the U.S. senate in April of 1964, it’s where Bourbon was first declared to the world to be a distinctive product of the United States [5]. It has sometimes been claimed that the resolution defined ‘Bourbon’ but that’s more than a bit of a stretch [6]. What it did do is set the stage for as yet, at the time, unwritten treaties and trade agreements that might be reached between the United States and other countries to protect the name ‘Bourbon’ and prevent it from being used to represent and sell products made elsewhere. The treaty I found from 1971 appears to have been the first instance of such an agreement.

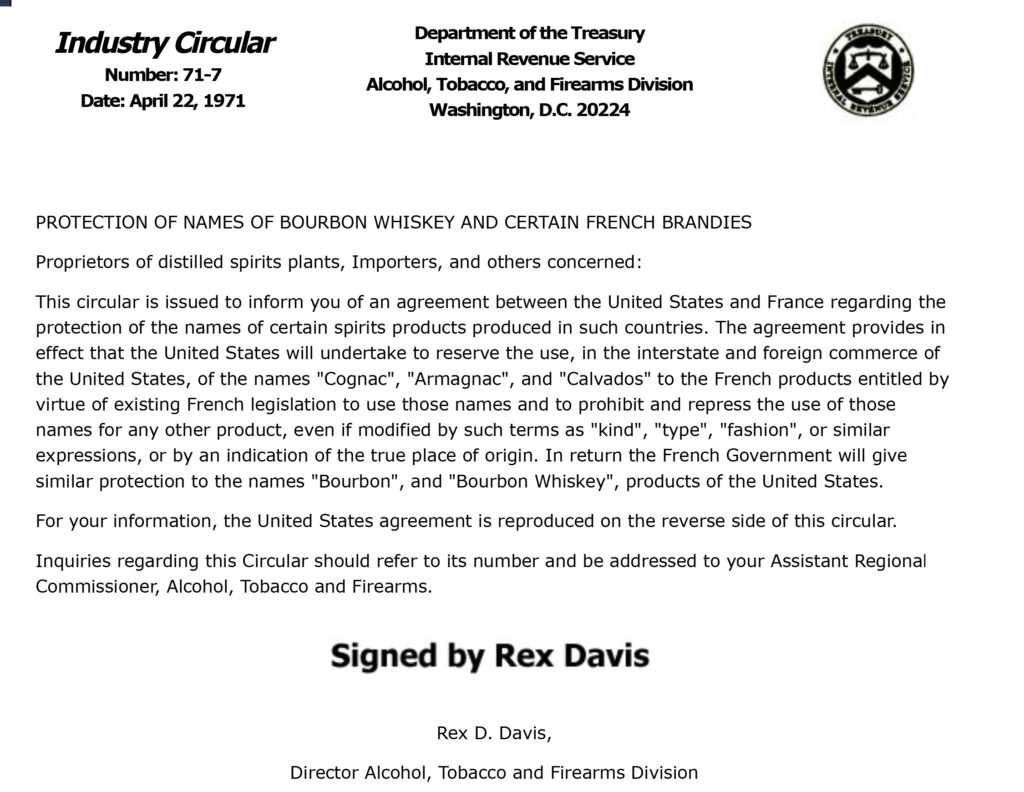

Typically trade agreements are reciprocal and involve some alike class of goods and/or services provided (or created) by each nation being protected. In this case, in return for protection of the spirit named ‘Bourbon,’ the United States agreed to protect the names of three spirits made in France, specifically brandies originating from distinct geographic regions in that country and made according to specific standards of identity. The three names were ’Cognac,’ ‘Armagnac,’ and ‘Calvados.’

The 1971 treaty took force as soon as it was signed. Almost immediately the TTB, the US government entity responsible for oversight of alcohol, sent out an Industry Circular to that effect. Below is a image of that notice:

It’s a Big World: What About the Rest of It?

A 2016 article in the Kentucky Journal of Equine, Agriculture, & Natural Resources Law, which discusses the case for making ‘Kentucky Bourbon’ a protected name [7], noted that by this time agreements similar to the one we made with France had been signed with other countries, notably Australia, Brazil, Chile, Germany, and South Korea. But ultimately many individual trade agreements would be subsumed under a number of much larger accords.

The first of these would be NAFTA, the North American Free Trade Agreement, executed in 1992 between Mexico, Canada, and the United States. Annex 313 of NAFTA provides similar reciprocal protections. In return for agreeing to protect the names ‘Bourbon Whiskey,’ and ‘Tennessee Whiskey’, the United States agreed to protect the names ‘Tequila’ and ‘Mezcal’ as distinctive products of Mexico [8], and ‘Canadian Whisky’ as a distinctive product of Canada.

In 1994, the European Union Distilled Spirits and Spirit Drinks Agreement was enacted between the United States and all EU member nations [9]. European Union members agreed to protect the names ‘Tennessee whisky/Tennessee whiskey,’ ‘Bourbon whisky/Bourbon whiskey’ and ‘Bourbon.’ In return the US agreed to protect the use of several product designations: ‘Scotch whisky,’ ‘Irish whiskey/Irish whisky,’ ‘Cognac,’ ‘Armagnac,’ ‘Calvados’ and ‘Brandy de Jerez.’ Interestingly this agreement explicitly states it does not supersede the earlier agreement made with France back in 1971.

And mixed into all of this are a variety of what I might call ‘super agreements’ in the form of things like TRIPS (The Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights) in 1994, agreed to by all member nations of what would eventually becomes the World Trade Organization (or WTO). And, ostensibly, what had been known as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (or TTP) back in 2016 would have also provided protections for the name ‘Bourbon’ between the United States and 11 other pacific-rim economies [10]. For better or worse, the United States withdrew participation from that agreement in 2017, pretty much bringing it to an end. This may have left the name ‘Bourbon’ in limbo in those parts of the world.

Bourbon from New Zealand, anyone? [11]

—

Notes:

[1] OK, I’m an old and I almost wrote ‘card catalog’ which of course was the analog precursor to the electronic versions we use today.

[2] And yes, I did find what I was looking for in those results. I hope to finish the piece in the next week or so.

[3] The collection itself is called United States Treaties and Other International Agreements, Volume 22.

[4] Weirdly, while both English and French language versions of the agreement were included in the collection, the title itself is only in English. I wonder if that chaffed the French Minister of Foreign Affairs (or Le Ministre des Affairs Étrangères) who signed this, someone named Maurice Schumann.

[5] Note that the US had already implicitly recognized Scotch whiskey, Canadian whiskey, and Cognac as distinctive products of their respective nations (UK, Canada, and France) as part of 27 CFR 5, where these spirits are called out by name.

[6] Similar claims are made for the so-called Taft Decision, published in 1909. Taft does help clarify some distinctions between whiskey made entirely from grain and water (AKA ‘straight whiskey’) and whiskey made by blending (or compounding) aged and neutral spirits together (AKA ‘rectifying’). However, the word ‘Bourbon’ appears no where in the text. It also had nothing to say about rules for mash bills, barrels, or aging, things that wouldn’t be taken up until after Prohibition.

[7] The article, titled The Proof is on the Label? Protecting Kentucky Bourbon in the Global Era by James Bonar-Bridges, is interesting all by itself. It explores in detail the question of whether and how ‘Kentucky Bourbon’ might become a globally protected name. This would be based on what’s usually described in the global trade lingo as a ‘GI’ or geographical indication. The article would seem conclude this would not be possible, at least at this point in time. Something to do with the result of what the author describes as ‘generalization’ of a product name.

[8] A couple of additional things to point out about our agreements with Mexico. First, there were at least two distilleries operating in Mexico, established during Prohibition, producing whiskey labeled and sold as Bourbon in the United States. So NAFTA would have been the end of any grey areas for those products. Second, and this is really pretty shameful: in the United States it remains legal to sell so-called ‘mixto’ agave spirits, which are the equivalent of blended whiskies but based on Tequila, using the name ‘Tequila’ on the label. This is illegal in Mexico and its circumvented by doing the bottling and labeling here in the United States. Consider that next time you see a bottle of Cuervo Gold.

[9] The UK has of course now exited the EU which led, in 2019, to a new agreement titled Agreement Between the United States of American and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland on the Mutual Recognition of Certain Distilled Spirits/Spirit Drinks, which unsurprisingly covered the same ground as the 1994 EU agreement.

[10] The 11 other TTP signatories were Australia, Brunei, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, and Vietnam.

[11] /jk Kiwis are too polite to do something like that. And we probably have a treaty with them that protects ‘Bourbon’ anyway.