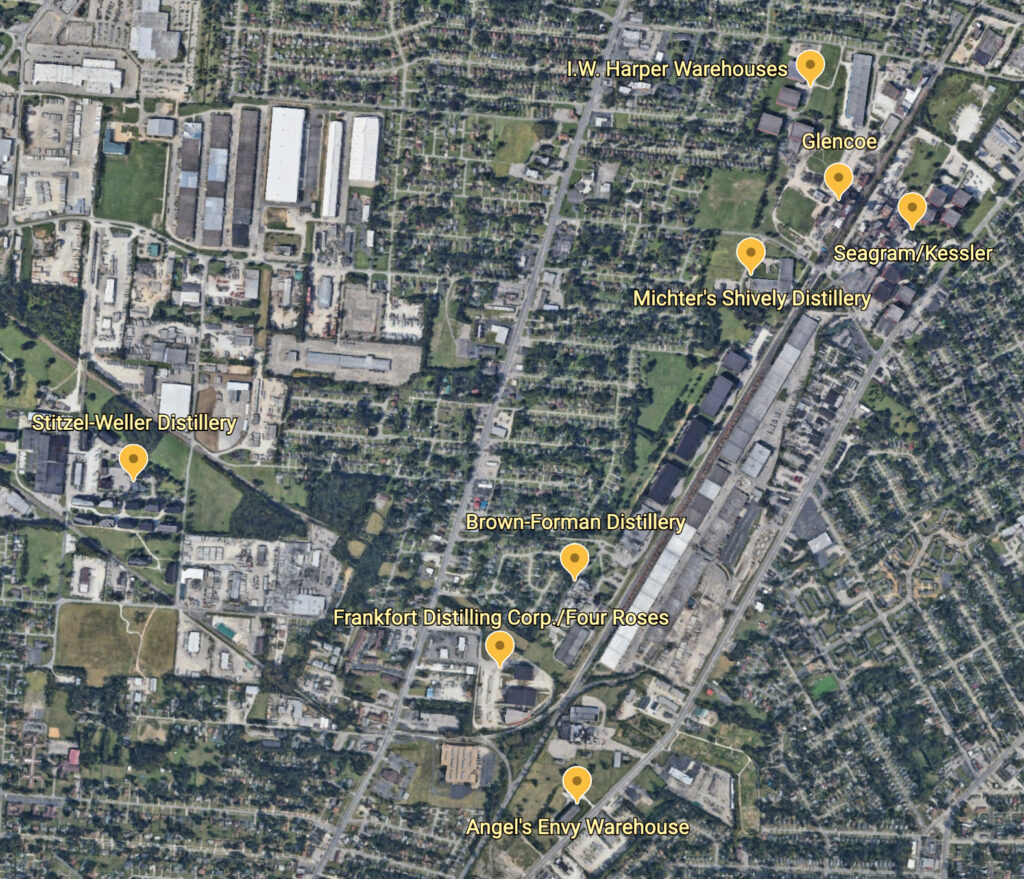

I already knew that Shively, a suburb of Louisville, was something of an archaeologic mecca for whiskey history buffs when I was shown photos of the old Seagram warehouses located there a couple of week ago. This was over post-dinner whiskey pours at North of Bourbon. I knew that before its demise Seagram had two distilleries in that area: one which had been owned by the Frankfort Distilling Corporation (AKA Four Roses) and a second which Seagram had built in the 1930s after acquiring the Kessler brand. I knew the some of the original Frankfort warehouses were still standing. I had not realized the Kessler warehouses were also still there. I had also not realized how striking and beautiful they were. I had been wanting to head over to Shively since moving to KY and take a look around. After seeing the Kessler photos, I realized it was time for a long overdue pilgrimage.

First, a respectful bow to those who came before me

Before proceeding with my story, I want to give some important credit here to the creators of a website I had discovered many years back when I was taking my first steps into the world of American whiskey. This is where had first learned about the existence of a number of distillery ‘ruins’ located in Shively.

The website in question is simply titled “American Whiskey” (AKA “John and Linda Lipman’s Adventures in Bourbon Country”). The URL was and remains www.ellenjaye.com, a phonetic portmanteau of the couple’s of first name initials, ‘L’ and ‘J’. It was started by the Lipmans in 1996 and while they’ve been silent for a long time, ellenjaye.com provides an incredible window into the American whiskey enthusiast landscape back in the ‘00s. To be sure, it was a kinder, gentler and less ‘rabid’ scene back then, when many distilleries didn’t have visitor centers (let alone tours) and hunting ‘dusties’ was just becoming a thing (and still a practical pursuit). There was also a lot more general interest in brand history and much less interest in collecting bottle for bragging rights (i.e. bunker building). I consider the posts at ellenjaye.com something of a treasure trove for anyone interested in relatively recent perspectives on American whiskey history.

For the most part, the site is a travelog of the visits the Lipmans made by car to a variety of distilleries located throughout the Ohio river valley during the early 2000s. They provide descriptions and photos of what they found (or in some cases, failed to find) along with fairly detailed historic background notes. In particular there’s an entire page dedicated to visits to defunct distilleries. It’s titled appropriately enough GHOSTS of WHISKIES PAST (yes, in CAPS just like that). It was here that I first read about what might be found in Shively, though at the time (2015) I was a long way from being anything of a whiskey historian and even a longer way from Kentucky. They made their particular Shively pilgrimage in October 2000, led by a then much less well-known (and younger) Mike Veach. The Lipmans and Veach became good friends during this time and remain so today [1].

So: an appropriately deep and grateful bow to the Lipmans, who explored Shively before me so many years earlier and who left such an excellent trail for me to follow.

And now without further fanfare, my story and a lot of photos.

Seagram at J. Kessler

The property at 2500 7th Street Road, owned by Seagram and operated as the J. Kessler distillery, DSP-KY 37, was opened in 1937 after three years of construction. It remained active until 1983 when Seagram closed it down. Apparently at one time it was touted as the largest distillery in the world, though a lot of what was made there was grain alcohol for Seagram’s many blended whiskies.

Like most of the old distilleries in this area, the still house is long gone. What remains are the warehouses and the buildings used for support operations like filling and dumping barrels, bottling and shipping/receiving [2]. Most have been converted into what appears to be mixed use commercial: offices and some light industrial stuff. There might also be some ‘artist lofts’ but I’m not 100% certain of that. Most notably one warehouse now serves as a drive-in truck tank wash. It’s built directly into into the first floor of one of the buildings, where presumably there had once been a loading dock. Kind of makes sense when you think about it.

One of the most striking architectural features of these buildings are the bas-relief signs to be found in the lintels the primary entrances to the warehouses and other functional buildings on the property. The entrances are framed in blocks of what appears to be fine grained unpolished stone, possibly the limestone colloquially known as Kentucky river marble. The signs are carved directly into the lintels. The lettering shows no sign of erosion or other degradation even though the buildings are over 70 years old. Here are a couple of examples:

There are also some ornate metal prosceniums (proscenia?) in front of the doors to what I imagine was the building that housed the administrative offices. Not entirely sure what kind of metal these are made from but the lack of green patina on the metal itself or on the surrounding stone makes me suspect it’s iron rather than bronze. (Or someone is taking extraordinary care of them.)

It would appear that at some point Seagram (or possibly the government) decided that the original warehouse designations, which used just single letters, were insufficient. New signage was added over the entrances using bronze letters anchored directly into the stone. Sometime later, possibly after Seagram shut the distillery down, the letters were removed. They had however been in place long enough to leave green stains in the stone. With a little patience and the right lighting these can still be read today. For example, over the entrance to Warehouse G, the text reads:

INTERNAL REVENUE

BONDED WAREHOUSE NO. 58

JOSEPH E SEAGRAM & SONS INC

Here’s what it looks like today, in an image I tweaked to increase contrast and make the lettering more legible:

It’s certainly possibly that the letters, once removed from the stone, were just discarded. However, I prefer to imagine that somewhere, in some storage closet in one of those old buildings, there’s a box filled with them. They’re just waiting to be rediscovered.

—

Notes:

[1] Veach actually wrote about his friendship with the Lipmans on his blog in 2016. Here’s the link if you’re interested:

Bourbon’s Unsung Heroes John and Linda Lipman. If you want to go even deeper down the rabbit hole, you can also find a number of posts made by the Lipmans, under the name ‘ellenj’ on bourbonenthusiast.com, another seminal website of that period. Be sure to check out posts by Veach (and his incredible timelines) and Chuck Cowdrey.

[2] There’s also a very lovely mansion-like building on the property that served as Seagram’s corporate offices. Today it’s occupied by a charity. Considering the attention put into detailing the exteriors of the warehouses, I would suspect it’s quite beautiful inside.

Pingback: A Pilgrim in Shively [Part II] – In the American Grain