(You can read Part I of this story here.)

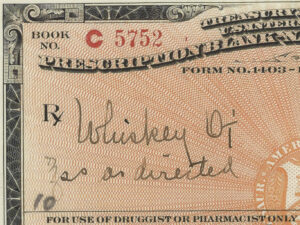

Frankfort Distilling Corporation AKA Four Roses or Didn’t you read the f$@k(^g sign?

The remains of what had been the Frankfort Distilling Corporation in its post-Prohibition incarnation are to be found at the junction of Dixie Highway and Ralph Avenue. Easy enough to find but, as it turned out, much harder to actually get a close look at, and thereby hangs a bit of a tale. Since I’m very familiar with the Four Roses brand, let me preface the notes from my unexpectedly dramatic visit with little bit of this distillery’s history.

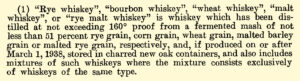

After the repeal of national Prohibition very few distilleries remained in good enough condition to be easily restarted. Some had been dismantled and anything of value (like copper stills) sold off as scrap. Other were simply shuttered and left to deteriorate. This had been the case for the Frankfort Distilling Corporation, which owned Four Roses. While they were able to sell (and purchase) existing stocks of whiskey using their medicinal permit, they had let the distillery itself, located in Frankfort, KY, go into disrepair. So after Prohibition they would need to find a new home.

Fortunately one of the other medicinal spirits permit holders, Stitzel, had maintained their distillery well enough to be restarted [1]. This meant they were able to provide contract services to distilleries like Frankfort immediately after repeal [2]. Fairly rapidly Stitzel decided they needed larger facility, and starting building a new home not terribly far from their current location, what would eventually become known as Stitzel-Weller. Once the new distillery was ready, the old distillery was sold to Frankfort. It is the remains of this distillery I believe stands today at the junction of Ralph Avenue and Dixie Highway in Shively.

Unlike the Seagram/Kessler campus, which was open and relatively easy to explore, the old Frankfort distillery was more or less fenced off. The current owners (who will go named) put up a couple of ‘No Trespassing’ signs on a perimeter fence that encircled the warehouses. However, there was a short access road from Dixie Highway leading up to the the fence and its gate was open to allow truck traffic to come and go from the property. I had already tried finding a way to approach the warehouses from the other side but train tracks and a lot of other businesses made that pretty impossible. So to get any kind of reasonable photos of the old warehouses (which are all that appear to remain) I had to make a decision: I either had to satisfy myself with taking pictures at a distance from Dixie Highway or drive onto the property, pretty much up to that gate, and hope no one was paying a lot of attention. There were plenty of places to park off road so it seemed possible. Also there was a large open field along one side of one warehouse, outside the perimeter fence. Emboldened by my experience at Kessler, I decided to take a chance and get closer.

Not every ruin is charming

As you can see from the photos I managed to get, the warehouses here were more or less just functional multi-story brick buildings, especially when compared to what I saw at Seagram/Kessler. The bricks on the outside were a kind of semi-hollow (hard to make out in the photos-sorry) and very coarsely textured. It made me think that perhaps there had been a cosmetic facing on the warehouses at some point, now long removed. I didn’t see any evidence of anchor points for such features so possibly what I saw is just how they had always appeared. And any of the original signs or placarding or purely aesthetic flourishes that might have been there originally were long gone. To make something of an analogy, if the buildings at Seagram/Kessler had been palaces, the ones here were more like the homes of average citizens. Nevertheless, during the 1930s, this is probably where Four Roses and other Frankfort brands would have been distilled and aged.

Intermission: The Pilgrim and The Bulldog

I managed to get fairly close to the warehouses without drawing much attention…or so I thought. On my way back to my car (parked in an open lot but behind a utility shed) I spotted a gentleman pacing back and forth by my vehicle, speaking into his cell phone. As I approached the car, he got off his call and immediately began to accost me.

Now I need to pause here because I want to be sure you understand that I understood I was by the strict definition of the term ‘trespassing’ doing just that. I can’t wiggle out of it. However, I was far from any of the building entrances or truck loading/unloading areas. I was also outside of the perimeter fence during my visit, only on the surrounding property. I also made no attempt to hide or keep out of sight. So…trespassing yes, doing anything really suspicious, no. Also I hope you can absolve me for my trespasses (ha ha) since I was a bit agog at the prospect of getting a look at these old historic buildings. Now…back to being accosted.

The gentlemen, whom I will now refer to as The Bulldog, laid right into me as soon as he saw me. I might say more than a bit abusively, with pretty salty language I won’t repeat. “What the @#!k I was doing on the property?”, I was immediately asked. I explained that I was a historian of American whiskey and that I believed this had been the site of a famous old distillery and that I was interested in taking a closer look. I honestly expected a modicum of softening in his demeanor once I stated my purpose. I was wrong. Instead I was further scolded for being on the property and for having failed to notice that photography was also explicitly forbidden. I guess it stated this on the ‘No Trespassing’ signs but I had not noticed. Also: photography? What exactly were they doing on this property anyway?

The Bulldog then directly threatened me with arrest, though there were no law enforcement officers in sight. I’m not sure what he expected I was going to do once he made this threat. Argue with him? Stand my ground and refuse to leave? Wow. No, I did what any reasonable human would do: I apologized profusely and said I was going. I was then told that I would immediately be arrested if I ever came back. I am choosing to leave out the various expletives that salted all of his final declarations. I replied that he didn’t need to worry about my returning. I smiled, got in my car, headed home and didn’t look back.

One last thing to add: Below is a screen shot of an image of the warehouses I made using google maps clever 3D feature. Pretty good if you ask me. And very detailed too, no? This makes the overheated reaction I got to taking a few photos even more of a head scratcher. Is there something they’re trying to hide from the public? Seems far fetched. Or perhaps The Bulldog simply takes his job more than just a bit too seriously. And unless I hear there’s really something exciting to see behind that fence, something left over from the original distillery, I have no plans for another visit, even with permission [3].

The mystery warehouse

As I mentioned at the start of this, Shively is something of an archeological wonderland for American whiskey history. Proving my point, as I drove down 7th Avenue Road, south of the Seagram/Kessler campus, I spotted a four-story metal clad warehouse sitting completely by itself in an open field, painted grey and stained with the traditional ‘dress black’ of Baudoina fungus. I turned down a short access road leading to it (and a locked gate) so I could get closer look. There were no signs on the locked gate to indicate who owned or might be currently using it. I then spotted a sign over the door and was able to use my phone’s camera to zoom in enough to read it:

Louisville Distilling Company

Warehouse [indecipherable]

DSP-KY 2022

KY Lic# 056-DSWS-1042

Easy enough to look up the DSP and learn this was being used by Angel’s Envy. I posted the photo to my instagram account (@intheamergrain) and tagged it to see if someone at the distillery might have more information one it. Amazingly enough, I got a reply from Connor Henderson (@kybourbonaire), whom I assume is Angel’s Envy founder Lincoln Henderson’s grandson. He confirmed that the warehouse had been purchased by Angel’s Envy in 2014 and that it could hold approximately 18,000 barrels. The warehouse is currently empty after the barrels it held were transferred to another location (which Connor did not reveal). It would be interesting to find out for who the warehouse had been originally built and when. Given the lineage of Angel’s Envy, a brand created by Brown-Forman’s former master distiller Wes Henderson, it would make sense that this would have have originally been a B-F property. What’s odd about that is this warehouse’s isolation, standing alone in an empty field, separated from the adjacent BF campus by a set of train tracks. Maybe there had been more warehouses here originally? If I find out more I’ll update this post.

Coda et al

While my goal was to visit former distillery sites, three other very significant distilleries continue to operate in Shively: Heaven Hill/Bernheim, Brown-Foreman/Early Times, and Michter’s. None of these three is open to the public [4]. Stitzel-Weller is also here but is only used for warehousing and tours. The tours at Stitzel-Weller are well worth taking, by the way, as you get both some up close look at their incredibly tightly spaced warehouses as well as the building that housed Julian ‘Pappy’ Van Winkle’s old office. It’s now a bit of a shrine to Bulleit bourbon.

I also couldn’t help not notice a few other interesting details while driving about:

- A major set of train tracks bisects Shively. You can see this in the first image at the top of Part I of this post. The tracks would have been built out, along with sidings and spurs, to provide access to and from the many distilleries that operated here in from the late 19th to mid-20th centuries. Now the tracks kind of uselessly subdivide the landscape in way that makes driving from point to point difficult. I can only imagine this impacts the quality of living in this area.

- I tried to get close to the Brown-Foreman distillery, formerly known as Early Times. But here, an actual security check point at the entrance made it clear there wasn’t going to be any causal opportunities to get closer. However, when I drove past it on its far side (near 7th Avenue Road) I did notice a lot of what appeared to be single story warehouses or, as the old-timers call them, flat houses. This made me curious whether they’re still in use and, if so, whether its Brown-Foreman using them or another distillery that’s leasing them out. If I learn something about them, I’ll let you know.

All in all, I would declare my trip to Shively a success. And with several other sites to visit (the I.W. Harper warehouses and Glencoe) I’m sure to return for another look around. Hopefully, with a little less drama.

Also, and to bring things into full circle, I was able to make contact with Linda and John Lipman, authors of ellenjaye.com, who’s accounts of their visit to Shively served as something of an inspiration for mine. Thanks again to these pioneers for leading the way!

—

Notes:

[1] Operations had actually been restarted in 1929 when the Federal government, realizing that existing stocks of whiskey were dwindling, authorized 1,500,000 more gallons to be made. Stitzel was the only distillery in a condition to make any of this whiskey.

[2] Brown-Foreman, another permit holder, found themselves in a similar position and so also relied on Stitzel to get going again.

[3] I debated with myself several times about including this incident in the story. I do think I pushed things a bit for the sake of a couple of photos and got in trouble as a result. If nothing else it serves as possible caution to other folks who might want to have a look at these sites themselves. Not everyone is enthusiastic about the history of the place where they work. The reception you receive won’t always be so friendly.

[4] Several years ago I was fortunate enough to visit both Heaven Hill/Bernheim and Michter’s, both by special arrangement. If you hadn’t noticed yet, I’m a bit of a distillery groupie.