Karl Raitz’ book Making Bourbon (which I’ve mentioned here previously) is a gift which keeps on giving. A footnote in the current chapter led me to a small book entitled The American Compounder or Cross’ Guide for Liquor Retail Dealers written in 1899 by Chas. Cross, self-proclaimed ‘Practical Chemist and Compounder.’ It turns out to be a ‘how to’ manual for the trade with special emphasis on ‘how not to be be ripped off’ by rectifiers. Cross’ states right up front:

“American manufacturers of liquors have no equals in the compounding of cheap liquors; their main object is to make them as cheaply as possible and sell them for all they can get, their profits running as high as two hundred per cent, depending on the knowledge, or rather, the lack of knowledge, of the retail dealers, to get those profits.”

Cross’ intent is to remedy that ‘lack of knowledge’ with the tips and tricks outlined in his guide. For example, I learned how a barrel may be constructed such that its gauged volume may be made to appear smaller or larger than its actual volume. The former technique was useful if one desired to cheat the government out of excise taxes due when the barrel is withdrawn from bond, while the later technique allowed unscrupulous wholesalers to cheat unsuspecting retailers buying whiskey by the barrel. Who knew?

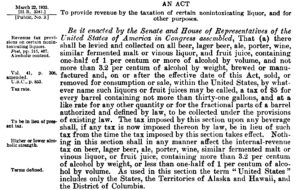

But the most interesting discovery I made in Cross’ book has to do with a limitation in some Federal legislation that had been passed just five years earlier. The Customs Law of 1894 provided a significant extension to the length of time a whiskey could be held in bond before excise tax needed to be paid, from three to eight years. However, it turns out there were a couple of serious problems with the law the way it was written. At least from the point of view of distillers and of retailers like Cross.

Employing some simple math, Cross shows how under the rules of the 1894 legislation it would likely be unprofitable to hold a barrel of whiskey in bond any longer than four years. At the time Cross wrote his book in 1899, these problems had just finally been addressed with the passage of the very verbosely named An act to amend the internal-revenue laws related to distilled spirits, and for other purposes (30 Stat., 1349), hereafter simply referred to as the 1899 legislation.

First, let me share my understanding of how I believe bonding and taxation in the 19th century worked. Now reading 19th century tax law is hardly something I can say to be an expert in but with persistence I feel I’ve gotten some sense of how it worked. Still, it’s possible the explanation I’m about to give is flawed. If that turns out to be the case, I do hope someone who notices this can set me straight. Here goes…

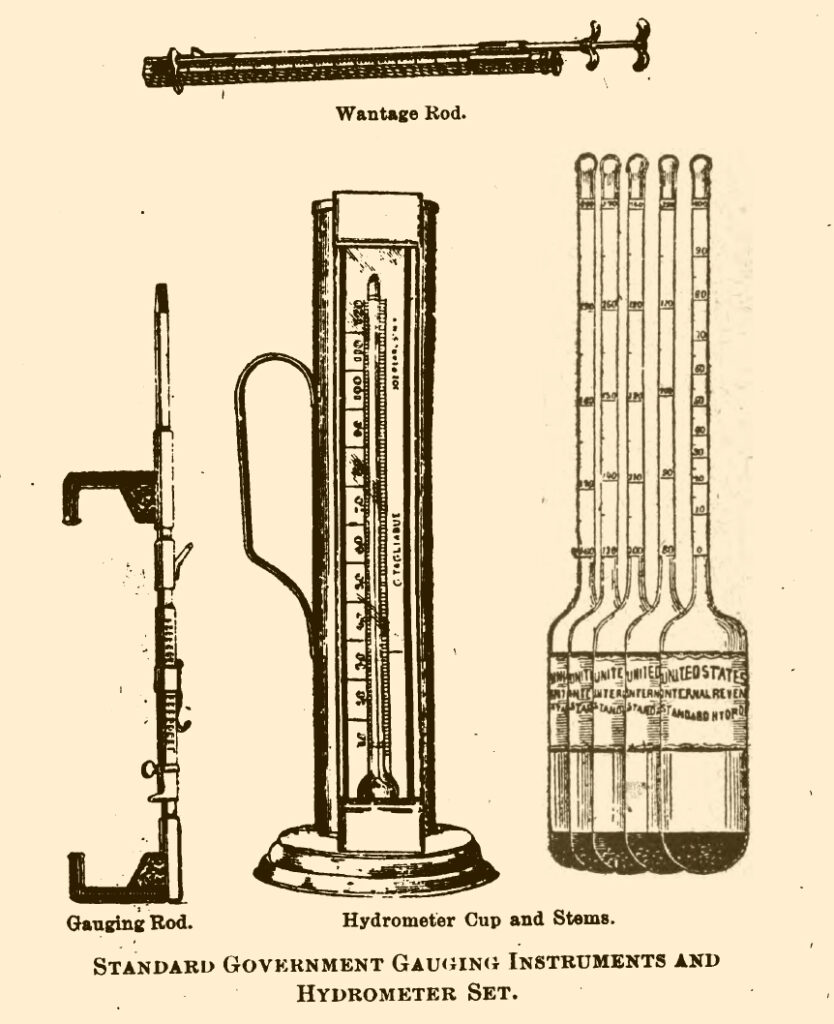

When a barrel of whiskey is entered into bond, it gets gauged, which means a government agent (‘Gauger’) will determine the volume of whiskey inside the barrel (given in wine gallons, which are actually just plain old gallons) along with whiskey’s proof. The Gauger then uses these numbers to calculate the number of proof gallons the barrel will yield, which is to say, the number of gallons of whiskey you’ll have to sell after the proof is adjusted to 100 (50% ABV) by diluting with water.

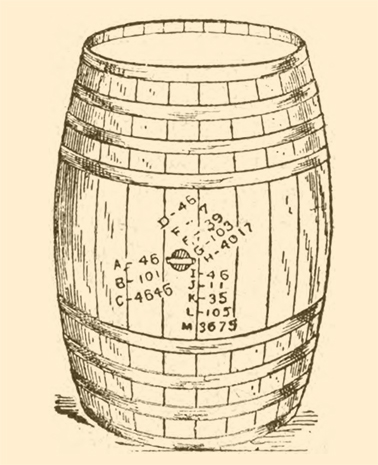

All this information is then turned into a record of entry into bond, inscribed by the Gauger on the barrel in a specific location near the bung. (See A, B, and C in the illustration below.) According to Cross, these were called ‘wheelings,’ a term I had not encountered before.

When the barrel is then later withdrawn from bond, some number of months or years later, the Gauger will measure the volume remaining in the barrel along with its proof (both will have changed during aging). Tax due is then calculated as follows:

- Take wine gallons recorded at time the barrel was entered into bond (A from the illustration below) and subtract the number of wine gallons lost while in bond (outage), up to the maximum outage allowance. This gives net wine gallons.

- Convert net wine gallons into proof gallons (based on regauged proof). This gives adjusted proof gallons.

- Tax is due on the adjusted proof gallons.

The Gauger will then record these exit numbers on the outside of the barrel, adjacent to the record of entry.

We should talk a little about this outage allowance.

Originally distillers had been assessed taxes on spirits as they came straight off the still. That’s fine if you were going to immediately turn around and sell the spirit. However, if your intent was to hold and age the spirit (ostensibly to improve it and to increase its value) then this was a pretty terrible deal. As whiskey ages you’re naturally going to loose some of it, as it gets absorbed by the barrel, evaporates, and/or the barrel simply leaks. That’s whiskey you’ve paid the taxes on but which you’ll never be able to sell.

Eventually two changes to the laws made it a little fairer for distillers.

First, if you were going to age whiskey it needed to be placed in a secure warehouse under government supervision to prevent any tampering. This is the act of entering it into bond and meant payment of tax could be deferred until you were ready to sell the whiskey, after giving it time to mature and increase in value. Second, an allowance was made to account for the natural loss of salable product during the time the whiskey was aging, so-called outage. Cross calls this ‘wantage,’ an alternate term for the same thing. The actual language of the 1894 legislation reads: “a loss of distilled spirits from any cask or package without fault or negligence of the distiller thereof.” Outage.

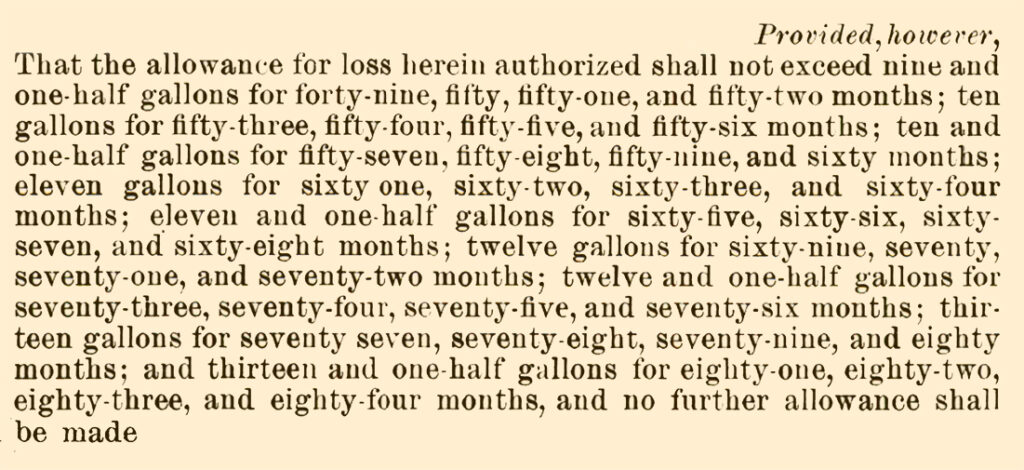

The allowed outages appear to have been based on some kind of ‘an average barrel can be expected to absorb/loose this much volume of whiskey per unit of time’ calculation. Basically, the longer the barrel remained in bond, the larger the allowance. I really don’t know how much actual science was involved in coming up with these numbers. It might have been more a matter of what people observed and reported over the years. Here are the outage allowances from the 1894 legislation:

(I’ve heard these referred to as the Carlisle Tables, which is a reference to House Representative John G. Carlisle, who would later be appointed Secretary of the Treasury and who, along with Edmund H. Taylor, Jr, helped to author the 1897 Bottled-in-Bond Act. But I digress.)

So outage allowances ensure that you don’t have to pay tax on whiskey that no longer exists/can’t ever be sold, as long as the loss can be attributed to normal causes, i.e. absorption/evaporation and leaks. However, if the actual (gauged) outage is greater than the allowed outage, tax is still going to be due on whiskey that no longer exists, i.e., it may represent some loss of profit on the barrel, depending on what it cost you to make and the price the whiskey can be sold for at the time it’s withdrawn from bond. Not a perfect system (and it often led to tax being due on some amount of non-existent whiskey) but better than what it replaced: paying tax at the time the whiskey was made.

Now, lets get to the problem with the 1894 legislation…

While the 1894 legislation extended the maximum time whiskey could be held in bond from three to eight years, it also stipulated that barrels would always need to be regauged at the end of four years. You wouldn’t need to pay the assessed taxes however until barrels were finally removed from bond, so the tax was still deferred. The problem is that no further allowance for outage would be made past the first four years. Since the volume of the whiskey inside the barrel would likely continue to drop while it was aging, you would now be liable for taxes on whiskey you could no longer sell. So leaving it in bond longer than four years made no fiscal sense under these rules. Fixing this was the intent of the 1899 legislation. This was done simply by extending the allowed outages to a maximum of eighty-four months or seven years. Here’s the extension:

Cross’ book was written just as the 1899 legislation was coming into force so unfortunately he couldn’t provide any evidence as to how the extended outage allowances were received by distillers and wholesalers at the time. Gauging records from the ensuing years, if we could get them, might provide an indirect means of determining the effects. We could see if more whiskey was being held in bond past the four year mark as a result of the change. But regardless of practical outcome, the 1899 legislation at least attempted to fix the shortcomings of the 1894 legislation. And the long tug o’ war between distillers and the federal government over taxation would continue regardless of that.

Et Alia

Just 12 years later, in 1911, representative distillers would come to Washington and give testimony before Congress looking for increases to the outage allowances. Distillers reported that they were still paying taxes on whiskey that had evaporated during bonding and which they couldn’t sell, i.e. the allowances were (still) too small. There would be complaints about changes in the size of barrels (i.e. they got bigger), in the quality of the oak used to make them (i.e. they leaked more), and in the effects of heat cycling warehouses (which the distillers’ claimed was now a highly common practice).

The distillers would get their allowance increase—though it wasn’t very much, just two extra gallons distributed over the course of eight years of bond—but it was something. Of course, we’re now less than a decade away from ratification of the 18th amendment and passage of the Volstead act. Distillers’ would soon have more serious problems than outages on their hands. And retailers like Cross would be out of business.

Pingback: On the Evolution of Souring – In the American Grain