[Author’s note: I haven’t forgotten about completing what I intend to be a three-part story on early guides to American whiskey one it’s done. Part I was already published but I’ve fallen behind in my reading of the book I want to cover in Part II. In the meantime, here’s a little bit of whiskey history trivia to tide you over.]

Now, a few words on looking for things. When you go looking for something specific, your chances of finding it are very bad. Because of all the things in the world, you’re only looking for one of them. When you go looking for anything at all, your chances of finding it are very good. Because of all the things in the world, you’re sure to find some of them.

– Daryl Zero

The above quote from the 1998 film Zero Effect (starring Bill Pullman and Derek Zoolander Ben Stiller) seems to well sum my experience of ‘looking for things’ having to do with American whiskey history, particularly the laws governing its production. Searching for ‘something specific’ can and has often led to a dead end.

This turned out to be the case a few years back when I decided to research the creation of our current standards of identity for Bourbon. More particularly, I was looking for any information that might be had on the process by which the regulations that we abide by today, in Title 27 of the Code of Federal Regulations, Subpart C § 5.22(b)(1)(i), had been formulated. I was also hoping to learn about the people who had been tapped to write them. Unfortunately, those words, and some of the standard itself, seemed to have just been created out of thin air, having never appeared in any previous document that I’ve been able to find. Similarly, of the authors and their identities, no trace remains.

Still, I haven’t yet entirely given up on this quest and I continue to look for clues. More importantly, that search continues to reveal other interesting aspects of our current Bourbon standard. I suppose Daryl Zero might say that of all the things about American whiskey that could be discovered, I’ve managed to find some of them.

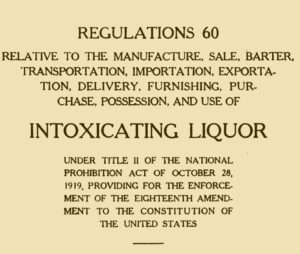

Title 27 of the Code of Federal Regulations (or 27 CFR, as we more succinctly refer to it today) was created as part of a more sweeping effort by the federal government to better organize (“codify”) all of the many, many (many!) rules and regulations that had been adopted since the formation of the republic. The codification effort was initiated in 1935, after the passage of the Federal Register Act. The act included a comprehensive framework into which everything was intended to be organized, what are referred to as “titles.” The first titles of the CFR were published just three years later, in 1938. Title 27, regulations relevant to tobacco, alcohol, and firearms, was one of these.

Prior to the CFR, each separate government agency simply published their rules and regulations using whatever format and organization they felt worked best in the moment. Even worse, updates to these publications made over time might result in them being renamed and the contents being reorganized. And updates weren’t always reflected in the revisions to the original, just a notice published separately. Finally, government agencies themselves might be reorganized, with responsibility for enforcement of regulations shifting from one agency to another, resulting in, again, changes to how documents were named and organized. This has made the process of tracing federal regulations as they have evolved, especially if they were created prior to 1938, into an often daunting and frustrating task.

Now prior to Prohibition the federal government really hadn’t had a lot to say about standards of identity for distilled spirits. There was the Bottled-in-Bond Act of 1897 followed almost two decades later by the relevant sections (AKA Food Inspection Decisions or FIDs) of the Pure Food & Drug Act in 1906 [1]. Mostly however it had been taxation that the government was concerned with. But immediately after the repeal of Prohibition in 1933, the effort to remediate this appears to have finally become a priority. The evidence of this work is only indirect, but in 1935 the Treasury Department published an early version of what would become the standard for spirits in 27 CFR. This appeared in the Federal Register of April 2nd, No. 14, page 92, titled TREASURY DEPARTMENT Federal Alcohol Administration, [Regulations No. 5] Labeling and Advertising of Distilled Spirits. The text of that publication (which I stumbled upon more or less by accident) was almost but not quite what would appear in 27 CFR three years later in 1938. However, between 1935 and 1938 one very significant substantive change was made to the nascent standard: the requirement for aging in new charred oak barrels. The difference is less than a sentence.

In 1935, the standard stated:

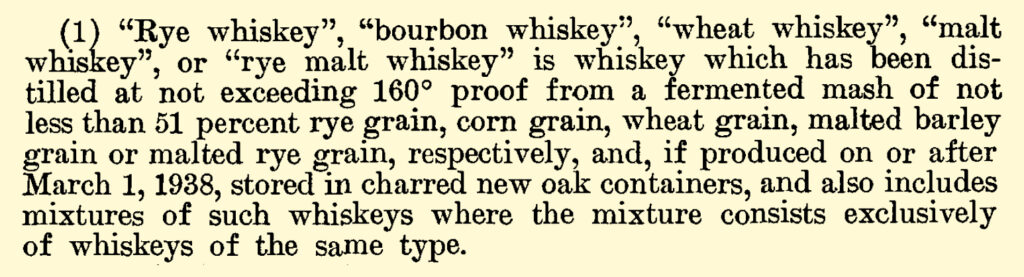

“Rye whiskey”, “bourbon whiskey”, “wheat whiskey”, corn whiskey”, “malt whiskey”, or “rye malt whiskey” is whiskey which has been distilled at not exceeding 160° proof from a fermented mash of not less than 51% rye grain, corn grain, wheat grain, corn grain, malted barley grain, or malted rye grain, respectively…

But in 1938, that same sentence continues:

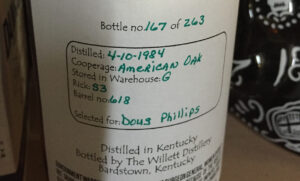

…and if produced on or after March 1, 1938, stored in charred new oak containers…

Now it would make sense that work on standard as a whole might continue after first appearing in the Federal Register. However, other than some reorganizing and minor rewording, the 1935 and 1938 versions of the core standard for whiskey was unchanged excepting the bit about the barrels needing to be charred, new, and made from oak. And clearly barrels besides charred and new (and possibly even oak) were being used, otherwise there’d have been no need to add in the grandfathering for whiskey made and warehoused prior to March 1, 1938.

I think it’s well established at this point is that the ‘framers’ of these requirements have remained anonymous and may well remain so forever. However the old catchphrase that states “follow the money” would lead one to conclude that representatives from the timber and the cooperage industries, both of whom would benefit from continued demand for new barrels, were likely behind this addition to the standard. And this is the generally accepted, or at least most often proposed, theory for how this came about.

But there’s also a much less cynical possibility. You could attribute this requirement to the adoption of what might have been viewed at the time simply as “best practices” for aging. In the absence of charring, whiskey develops very little to no color and has a harder time absorbing aromas and flavors from the oak. And whiskey aged in used cooperage would also have been known to take longer to reach maturity. Looking at it this way also requires much less paranoia about behind the scene influences by those with vested financial interests.

Unfortunately, we’re unlikely to ever know how things unfolded between 1935 and 1938 and what discussions and events lead us to ‘charred new oak containers.’ Which is really a shame because it would be great to know more about the people who stepped forward to draft the text of these standards. I’ll keep looking and hopefully of all the things about American whiskey that remain to be discovered, I’ve manage to find at least a few more of them in the process.

—

Notes:

[1] I’m choosing to more or less ignore the so-called Taft Decision in 1909, primarily, because it wasn’t a law and only indirectly resulted in changes to regulations that were already the purview of the Pure Food & Drug Act.