Sometimes it feels like every road leads back to 1897!

In the Beginning…

Most, if not every, American whiskey fanatic is by now familiar with the category of ‘bottled-in-bond’ spirits [1]. Originating with legislation passed in 1897, the act (championed by the infamous brand promoter E.H. Taylor) established the very first standard of identity for spirits produced in the United States. That standard is typically expressed in terms of four straightforward ‘rules,’ as follows:

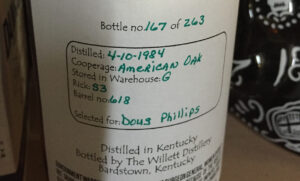

- The spirit must have been distilled at one distillery, during one distilling season.

- The spirit must be aged for at least four years [2].

- The spirit must be bottled at 100 proof (50% ABV).

- The only legal additive to the spirit is water.

Simple enough.

However, a close reading of the 1897 act actually reveals what amounts to a fifth requirement in order for a spirit to be bottled in bond. Here’s the relevant text (emphasis is mine):

[The distiller]…may remove such spirits to a separate portion of said warehouse which shall be set apart and used exclusively for that purpose, and there, under the supervision of a United States storekeeper, or storekeeper and gauger, in charge of such warehouse, may immediately draw off such spirits, bottle, pack, and case the same…

Source: Bottled in Bond Act of 1897 (29 Stat. 626)

In other words, in addition to meeting the other four requirements, a distillery also needed to set aside a place on the distillery grounds (initially inside a warehouse), along with the necessary equipment, where barrels of whiskey (if that was the spirit being bottled) could, under the supervision of a government agent, be gauged for taxes, dumped, mingled, proofed down, bottled and then packaged. Eventually this dedicated facility would become known as a distillery’s ‘bottled-in-bond department’ [3].

The requirement for a bottled-in-bond department had an interesting but possibly unintended consequence for distilleries: it created two classes of spirits each of which had to be managed separately by the distillery. First were tax-paid spirits [4], on which no special constraints were placed regarding how they might be mingled, proofed, and bottled (including first removing them, still in the barrel, from the distillery grounds before doing any of this). Second, and new, were spirits destined to be bottled-in-bond, which in addition to the first four requirements of the 1897 act, also had to be processed in the bottled-in-bond department located on the distillery grounds and whose operation required supervision of a government agent [5].

While the availability of relatively inexpensive mass produced bottles in the 1870s had led to increased adoption of distilleries bottling their own spirits, it would still have been a relatively new trend in 1897, especially given the slump in the trade which occurred less than a decade earlier. A distillery wishing to bottle-in-bond that had never bottled spirits before this would first need to invest in the equipment required to do so and install that equipment inside a warehouse designated for this purpose. And distilleries that had already been bottling tax-paid spirits on site either needed to invest in a second in-warehouse bottling facility or switch to bottling only in bond going forward [6]. In either case, establishing a bottled in bond department would have represented a significant cash investment to a distillery. So this fifth requirement may in fact explain the relatively slow initial adoption of the 1897 standard, despite the availability of spirits which otherwise meet the act’s other criteria [7].

The Great Revision

The provisions of the original 1897 act, including the requirement for a separate bottling in bond department, stood more or less unchanged for eighty years. That span included passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1909, the 13 years of Prohibition (1920 to 1933), and finally the establishment of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) in 1936 [8]. The passage of the Distilled Spirits Tax Revision Act finally changed that in 1979. This act resulted in four very significant changes to the law [9].

First, the act redefined the meaning of ‘bonded premises’ from the inside of one or more warehouses on the distillery property, to any suitable building on the distillery property. This immediately eliminated the need for and notion of a separate ‘bottled in bond department’ for bottling spirits in accordance with the provisions of the original 1897 act. In effect, going forward, all spirits became ‘bottled in bond,’ at least as far a taxation was concerned.

Second, it clearly separated the method for assessing and paying taxes on spirits from the core requirements which were used to qualify them for distinctive labeling as a ‘bottled in bond’ product. Taxes would now be assessed on all spirits at the time they were withdrawn from bond for bottling, regardless of how they were going to be labeled. If you wanted to qualify for ‘bottled in bond’ labeling, you would still need to conform to the core 1897 requirements, now recorded in regulations located in 27 CFR [10].

Third, the 1979 act also eliminated limits on the time a spirit could be held in bond before it had to be withdrawn, assessed for taxes due, and those taxes paid to the government. Bonding periods, the time a spirit could be held for aging before taxes would be assessed on it, were first implemented in 1880. The length of the bonding period (initially only one year) had been a point of contention between the federal government, which derived significant revenue from these taxes, and the distilleries, who were dependent on aging to derive maximum value from their products. By 1958 the maximum bonding period had been extended to 20 years by passage of the Forand Act. Now all spirits, whether they’d eventually qualify for bottled in bond status or not, could be held in bond until the distillery chose to withdraw it [11].

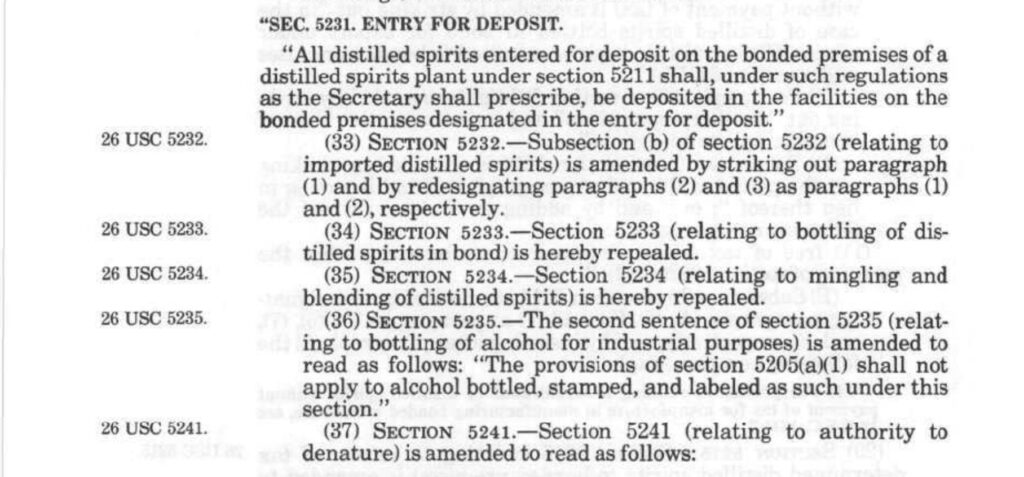

Finally, 1979 act deleted the key four ‘bottled in bond’ identity requirements from the tax code (26 CFR), technically ‘repealing’ much of the 1897 act. At first this sounds kind of dire, however by this time these same requirements had also been incorporated into the standards of identity found in 27 CFR so removing them from 26 CFR had real no legal effect, being more of a bit of house keeping than anything else. The tax code had never been the right place for those requirements in the first place. The 1897 act had very carefully been written to separate the identity standard it established from taxation.

Why These Changes at This Time?

As to the question of why these changes happened when they did, one just needed to look at the state of global whiskey demand, which was at an all time low. Everyone in the whiskey trade would have been looking for ways to reduce operating costs. Eliminating the need for separate bottling lines for tax-paid and bottled-in-bond whiskey would have been one way to accomplish that. Distilleries would also, once again, have been concerned about tax liability on the glut of aging stocks of whiskey as they were approaching the 20 year maximum for deferring taxes. Coming at a time when demand for whiskey was close to an all time low, paying those taxes would have been burdensome, possibly disastrous.

As to the how of the change, it is hard not to think about Louis Rosensteil and the so-called Bourbon Institute, a trade advocacy group, who’s lobbying in Washington resulted in Senate Concurrent Resolution 64 in April of 1964 which declared Bourbon a distinctive product of the United States. It was also Rosensteil, back in 1958, who was instrumental in getting the bonding period extended from eight to 20 years, thereby heading off financial disaster as the enormous amount of whiskey speculatively distilled for and then unused by the the Korean Conflict neared its eighth (and taxes-due) birthday.

Rosensteil was dead by 1979 but the Bourbon Institute, which had merged with two other lobbying groups in 1973 to form the Distilled Spirits Council of the United States (DISCUS), continued on without him. It’s not hard to imagine DISCUS had advocated for many of the changes in the 1979 act, especially the elimination of a fixed bonding period. This hardly seems coincidental, this set of changes coming almost exactly 20 years after the passage of Forand in 1958.

—

Notes:

[1] I write ‘spirits’ and not just ‘whiskey’ because, lo, it’s possible to produce almost any distilled spirit in accordance with the bottled-in-bond standard, including gin and even vodka. Imported spirits can also qualify for bottled-in-bond labeling, though the rules are slightly different for these. The point here is simply that the category is wider than most people realize.

[2] The minimum age requirement wasn’t part of the 1897 original legislation. It appears to have been added in March of 1911 as part of a more sweeping piece of legislation known as AN ACT To allow the bottling of distilled spirits in bond.

[3] The earliest use of this description I’ve been able to locate comes from 26 CFR (not 27) published in 1940, under the formal and lengthy title Regulations 6, Bottling of Distilled Spirits in Bond, also referred to as Title 26 Internal Revenue, Chapter I—Bureau of Internal Revenue, Subchapter C—Miscellaneous Excise Taxes, PART 188—BOTTLING OF DISTILLED SPIRITS (OTHER THAN ALCOHOL) IN BOND. It appears under Article III, Definitions, Section 188.3.

[4] At the time of the 1897 act, current regulations allowed for a maximum bonding period of eight years, after which taxes would be assessed and due to the government. A discount was applied to the tax based on how long the spirit (whiskey) had actually been held in bond, possibly less than the full eight years, to account for loss due to evaporation and leaks in the barrel over time. (See any of a number of my previous posts for discussion of this aspect of American whiskey history.) Once taxes had been paid, the distillery was free to do with the whiskey as it saw fit: bottle, resell, or even continue to age it.

[5] Ultimately procedures would be defined that enabled bottled in bond spirits to be removed from the distillery grounds while still ‘in bond’ (i.e. under government supervision) to a separate bottling facility. Most distilleries operate this way today.

[6] Procedures for temporarily using the bottled in bond department for a bottling tax-paid and bottled in bond spirits was eventually created, along with another procedure for switching back. That can be found in Article IX of 26 CFR, PART 188 (cited above). It naturally involved completing a bunch of paperwork and then approval of a government agent.

[7] It’s worth asking the question of just how unintended this was. The act was of course the brainchild of the businessman/distillery operator E.H. Taylor and his business partner, then Secretary of the Treasury, William Carlisle. The act’s primary provisions weren’t entirely altruistic as they specifically disadvantaged competitors like I.W. Berheim who as blenders/rectifiers, would be unable to bring a compliant product to market. But this fifth requirement also have prevented distilleries without their own on-site bottling facility from taking advantage of the new standard, even if they had stocks otherwise qualified stocks of whiskey on hand. It’s not entirely clear whether Taylor’s own O.F.C. distillery in Frankfort had a bonded bottling facility. The promotional pamphlet Taylor wrote for distillery and published in 1886 does state they had direct supervision over bottling so it’s possible they did.

[8] Specifically, it’s the 26th and 27th volumes of the CFR that the provisions of the original Bottled in Bond Act were ultimately enshrined with oversight by the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB), part of the Treasury Department.

[9] The 1979 act also started the phase out of the ‘joint custody’ system for direct oversight of distillery operations. The TTB would no longer require the presence of an on-site government agent or the use of government approved and controlled locks on bonded areas of the distillery. (Plus the entire plant was now considered to be ‘bonded’ not just warehouses and bottling areas). This was likely more of a matter of cutting costs rather than a reflection of new found trust between the TTB and distillery operators.

[10] Yes, this is a little confusing but the source of that confusion really dates back to decision in the original 1897 legislation to label this new class of spirits as ‘bottled-in-bond’ in the first place. A more accurate (if verbose) description would have been ‘bottled under the supervision of the United States Government in accordance with the standards of legislation passed in 1897 to ensure authenticity and purity.’ Holding the spirits in a bonded warehouse was just one part of that supervision. How the taxes due on the spirit were assessed and paid as they were removed from bond is really a different matter. In fact, as I am fond of pointing out, the 1897 act avoids saying anything specific about taxation, referring wisely instead to then current tax legislation passed in 1894.

[11] A strange thing about this particular provision of the 1979 act is that it was not mentioned in the official change summary sent out by the Treasury Department in October of that year to all distilled spirits producers. (See: Industry Circular 79-12.) Given the long history of friction between the federal government and distilleries over how long taxes due on aged spirits could be deferred (with distilleries always begging for longer deferrals and more discounts), this seems like a particularly odd omission.

![Read more about the article A Pilgrim in Shively [Part II]](https://americangrain.stream/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/IMG_2819_FourRoses_Warehouse01-300x225.jpg)