Researching the Bottled-in-Bond Act of 1897 was probably the first bit of historical research I did after I became deeply interested in American whiskey. The ‘rules’ for a bottled-in-bond whiskey were easy enough to learn—they were published on several websites—but I wanted to read the words of the act itself, the original language. It took a little perseverance and required what would be just the first of many forays into congressional records. Along the way, I discovered that the legislation was actually called (weird capitalization as shown) An Act to Allow the bottling of distilled spirits in bond (March 3, 1897).

Actual text in hand, I discovered (among other things) that the act didn’t specify a minimum age requirement for the spirits to be bottled at. It only included a “pointer” to the Customs Law of 1894. The often quoted four year minimum age requirement would come later in the form of a minor amendment. But that’s not what I wanted to write about today.

My real topic is the question of who was first to market with a bottled-in-bond (BIB) whiskey. When I did my research in 2017, I would have thought this would be something already well known. That turned out not to be the case. It’s certainly not documented in anything I’ve read since then. I also would have expected an immediate flurry of market entrants right after the legislation came into effect in 1897. There would have been plenty of whiskey already held in bond that would have qualified for the designation. That, too, turned out not to be the case. So what did actually happen?

Before going any further, I should start by stating that I am of an age where I can remember a time before the web, before search engines, and before the seeming ubiquity of having everything you’d ever want to know at one’s fingertips, instantly. (Or at least the illusion that you can.) And one thing living through the transition has taught me is that it pays to be patient and persistent, because if you wait long enough, eventually everything you’re looking for shows up. (Now whether what you find is true or not, that’s another question.)

The Obvious Candidate?

Back in March I got asked to tutor the manager at a local bar on the history of BIB whiskey. In the course of revising and expanding the notes I already had on hand, I came across a series of four articles about E. H. Taylor, Jr. that had been written by Chris Middleton, Board Member at New World Whisky Distillery, where Starward malt is made. The series had just recently been published in The Whiskey Wash, October 2021.

In the second part of the series, titled The Topmost Years, Middleton describes the run up to and the passage of the BIB act, which Taylor had a direct hand in creating and which he had eagerly anticipated. He writes:

“No sooner had Taylor received the green tax stamps from the Government printer to adhere over the corked bottles, he secured an order of 10,000 cases of Bottled in Bond from his Chicago agent in September 1897.”

Now, if you (or I for that matter) had been asked to guess who would have released the first BIB whiskey, there’d be no better candidate than Colonel E.H. Taylor, Jr. Right? And here finally is what appears to be the ‘smoking gun’ proving it. Unfortunately, Middleton gives no citation for the source of this information. Nor does he state which label was used for this bottling or where the barrels for these 10,000 cases of BIB had been aged. Or where his ‘Chicago agent’ sold them, for that matter. And While Taylor had regained ownership of the Old Taylor distillery two years earlier in 1895, I have to wonder if it had sufficient stocks in bond to fulfill such a large order. [1] I did try contacting Middleton a few months back asking him about this, but never got a response. But hey, the patience and persistence rule of the internet remains in effect.

“Here’s a Novelty”

I’d like to end this by putting forth another possible contender for title of earliest known BIB. But it’s such an odd item that, it too, merits some healthy skepticism.

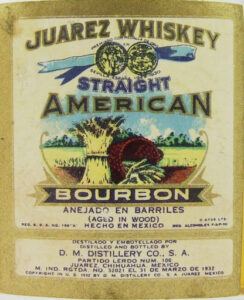

This ad appeared in a 1901 issue of the trade publication The Wine and Spirits Bulletin: [2]

The label, if it’s to be believed, states this was distilled in 1882, which would mean it had to have been bottled in 1898, the year after the BIB act became law. This might certainly qualify it as the earliest known BIB whiskey—certainly the earliest ad for one I’ve been able to find. But there’s a twist: the label also states it was “repacked in bond at the Customs Bonded Warehouse of the Louisville Public Warehouse Co.”

I could be wrong about this, but, a customs warehouse would seem to imply this whiskey had been initially sent overseas to be aged and then re-imported while still in bond before being bottled. Whiskey shipped to and then held in bonded warehouses located overseas (yes, there were such things) and then re-imported before being bottled was subject to a flat tax regardless of how long it had been aged. That flat tax was less than what would have been due if the whiskey had remained in a bonded warehouse in the U.S. for the same length of time. This was actually a common practice before the passage of the Customs Act of 1894 which lengthened the bonding period to seven years. [3]

Still, a whiskey this old, whether BIB or not, does stretch the limits of credulity for this particular time in history. Even by today’s standards, this would be a pretty old bottling. So, another candidate that should be taken with a grain or two of salt.

Thoughts, anyone?

Addenda

It occurred to me the morning after I posted this to consult Bourbon in Kentucky by Chester Zoeller (Butler Books, revised 2015) regarding the identify and history of the Louisville Public Warehouse Co., which is listed on the label for that mysterious Mammoth Cave 16 year old BIB. Indeed, Zoeller describes it on page 118, indicating August G. Coldewey (listed on that label) served as secretary, treasurer and manager of this warehouse. There was no distillery associated with this warehouse and it was used to hold whiskey purchased by individuals for investment purposes. They also received goods from customs warehouses, which I proposed as a possible origin for the whiskey in this very old bottling. Alternatively, the barrels in question might simply have been abandoned by their owners, which could also explain the excessive length of time they had been held in bond. Of course, taxes would have to have been paid on the whiskey first. Assuming the barrels had been re-gauged at four years (as per the Customs Law of 1894) and assuming the amount of whiskey in the barrels continued to dwindle, that must have been some very expensive Bourbon!

—

Notes:

[1] Assuming 6 bottles per case, that’s 60,000 bottles of BIB whiskey. That’s a lot of bottles for which not a single photo or advertisement appears to exist.

[2] Established in 1886/87 by George R. Washburne in Kentucky, The Wine and Spirits Bulletin (WSB) was published initially weekly then monthly right up until Prohibition. Most of what you find in it are short form business reports from various market regions in the Ohio valley, production and sales statistics, along with editorials on current events and trends. And, like any good trade rag, it’s also chock full of advertisements. I could probably write an entire article on the coverage provided by the WSB in the run up to Prohibition as the ‘Drys’ gained traction and political power first locally then nationally, culminating in the ratification of the 18th amendment. The distillery trade seemed unable to take the possibility seriously until it was really too late. Talk about being blindsided.

[3] Coincidentally, I learned about this particular bit of whiskey history from Chris Middleton’s articles. Taylor apparently not only made extensive use of this particular tax dodge but he helped to engineer it.