Anyone who’s taken the time to work their way through Karl Raitz’ book Making Bourbon: A Geographical History of Distilling in Nineteenth-Century Kentucky (University of Kentucky Press, 2020) [1] cannot fail to be struck by his academic rigor and dedication to constructing his narrative from a wide variety of primary and secondary source materials. In other words, he doesn’t speculate. So you can imagine my surprise when I came across the following statement in his chapter on legislation and law regulating the manufacture of distilled spirits (‘External Control’):

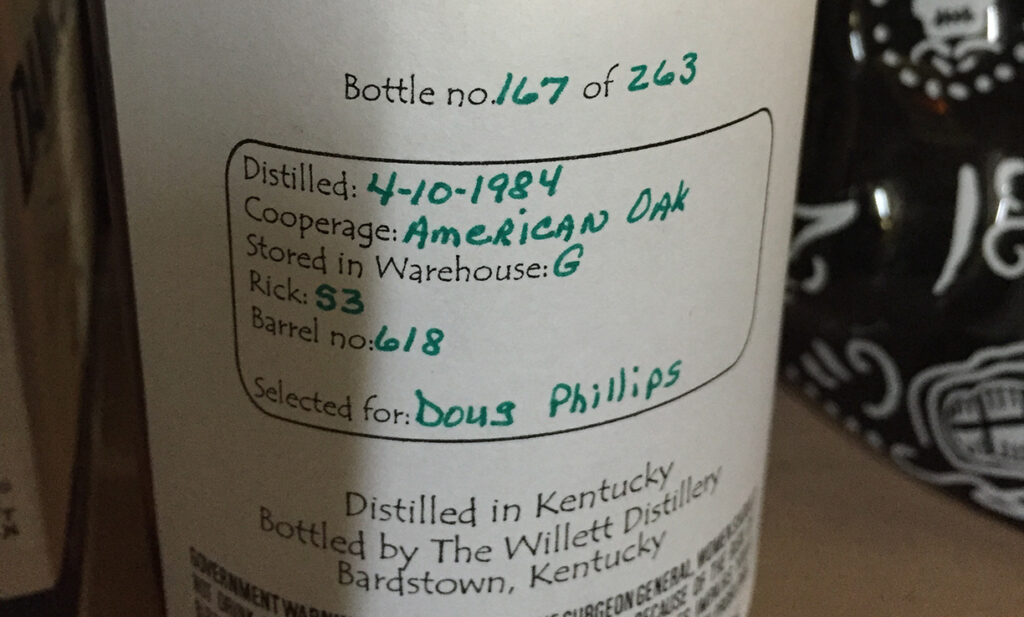

“Creative distillers did not ignore the barrel-branding process or the transformation of spirits from anonymity to individuality. Rather they carried it forward into the twentieth and twenty-first centuries by identifying certain barrels with superior flavor characteristics and decanting the contents into numbered bottles as ‘small batch’ and ‘single barrel’ bourbons for sale at premium prices.”

— Making Bourbon, ‘External Control and Landscape’, pp 275

What the what?

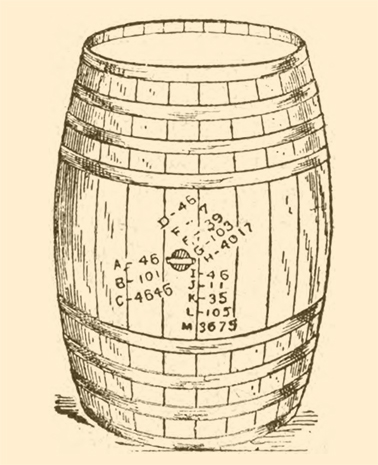

Now, what Raitz had been discussing up until this point was pretty cut and dry: the use of standardized markings (‘wheelings’) placed on barrels by Internal Revenue Service agents, known as Gaugers, to track and asses excise taxes that had to be paid before the whiskey inside could be sold, i.e. an external control. Prior to the adoption of this tracking system, barrels were more or less interchangeable with the likely exception that the distiller (or broker on who’s behalf the barrel might have been filled) may have branded his name on the barrel head, possibly along with the date it was filled. Otherwise, barrels from the same source were kind of fungible, with one being considered the same as another. And that’s often how they were sold and traded. [2] The addition of these marks provides for the first time an intimate record of changes to whiskey in proof and volume at the granularity of a single barrel.

But Raitz, so surprisingly, suggests a ‘through line’ from these very practical marks scribed on barrels for the purpose of calculating excise taxes to the modern marketing creation of ‘small batch’ and ‘single barrel’ Bourbons. And I have to say, I think Raitz is on to something. Now obviously some of the necessary connections were likely already being made, at least to the extent that the market was identifying the distillers making better whiskey, increasing demand (and price paid) for their barrels. The marks with the name of the distillery, however, go a step further, and imbue a single barrel with the possibility of a unique (and traceable) identity, from when it’s initially filled until mature and deemed ready for bottling. .And some barrels are going to be better than others. It then becomes just a matter of time before someone (probably in marketing) is going to see a way to exploit this new characteristic. Viewed this in this light, today’s frenzy of ‘private barrel picks’ would appear to be directly (and strangely) attributable to the enforcement of 19th century tax law.

A step further…?

It occurred to me that there might be yet another implication of the marks (and bonding in general). Once gauged, distillers would need to keep closer records on where barrels were put into the warehouse, as well as for how long—which by 1894 could be eight years. And as warehousing started to offer a wider variety of maturing environments (different building materials, different floors) these records, along with the marks, would make it possible to begin correlating barrel quality with warehouse location. So the marks might have also created the potential for a distillery to identify warehouse ‘sweet spots’ (AKA ‘honey holes’). Again, like the case for ‘single barrels’, people were going to figure this out eventually. But perhaps yet another unintended consequence of taxation was to help identify this phenomenon. It’s nothing if not fun to speculate.

—

Notes:

[1] I’m still not done but hopefully by the end of this year. I’ve got a couple of other books already in the queue.

[2] There is also the matter of distillery receipts which I was under the impression could be physically affixed to a barrel as an indication of ownership during the time it was held in bond. But I am uncertain how common this practice actually was. Would love to hear from someone who’s done more research into this.