(It’s not that kind of date!)

One of the most iconic and recognized photographs of the 20th century is Alfred Eisenstaedt’s V-J Day in Times Square, AKA The Kiss or more informally just “the photo of the sailor kissing the nurse.” (NB I am consciously choosing to not include the photo in this post.) It was taken 14th of August, 1945, shortly before the anticipated announcement that the Japanese had surrendered, thus ending that part of World War II. People leaving work started to spontaneously congregate in Times Square in what would become a huge thronging mass of celebrants, akin to the New Year’s Eve gatherings the square was already famous for, only under the early evening sun of summer. Eisenstaedt arrived with his camera and captured several shots of the soon to be famous though entirely anonymous couple. One week later they appeared on the cover of Life magazine and the rest, as they say, is history.

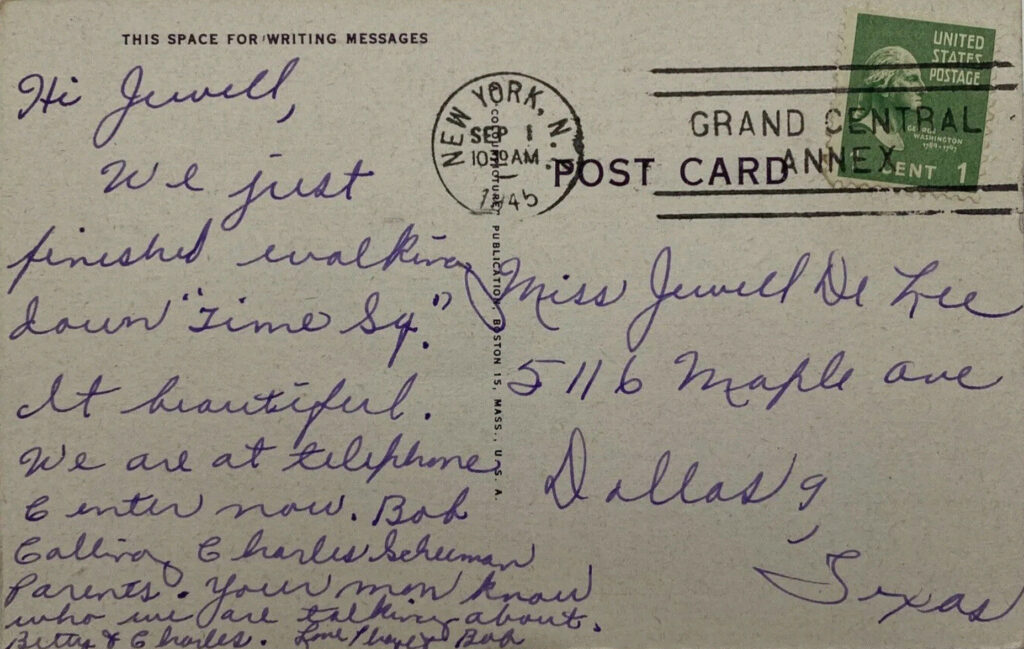

Somewhat incidentally this same photo captured another, though certainly lesser, iconic image: the enormous Four Roses advertisement that presided over the north end of Times Square for many years. It was for this reason that the Eisenstaedt photograph was included in the 2019 book Four Roses, The Return of a Whiskey Legend by Al Young, Senior Brand Ambassador, now sadly passed away. Those giant letters and the roses flanking them provided an illustration of just how successful and well known the brand became in the years following the repeal of Prohibition in 1933 [1].

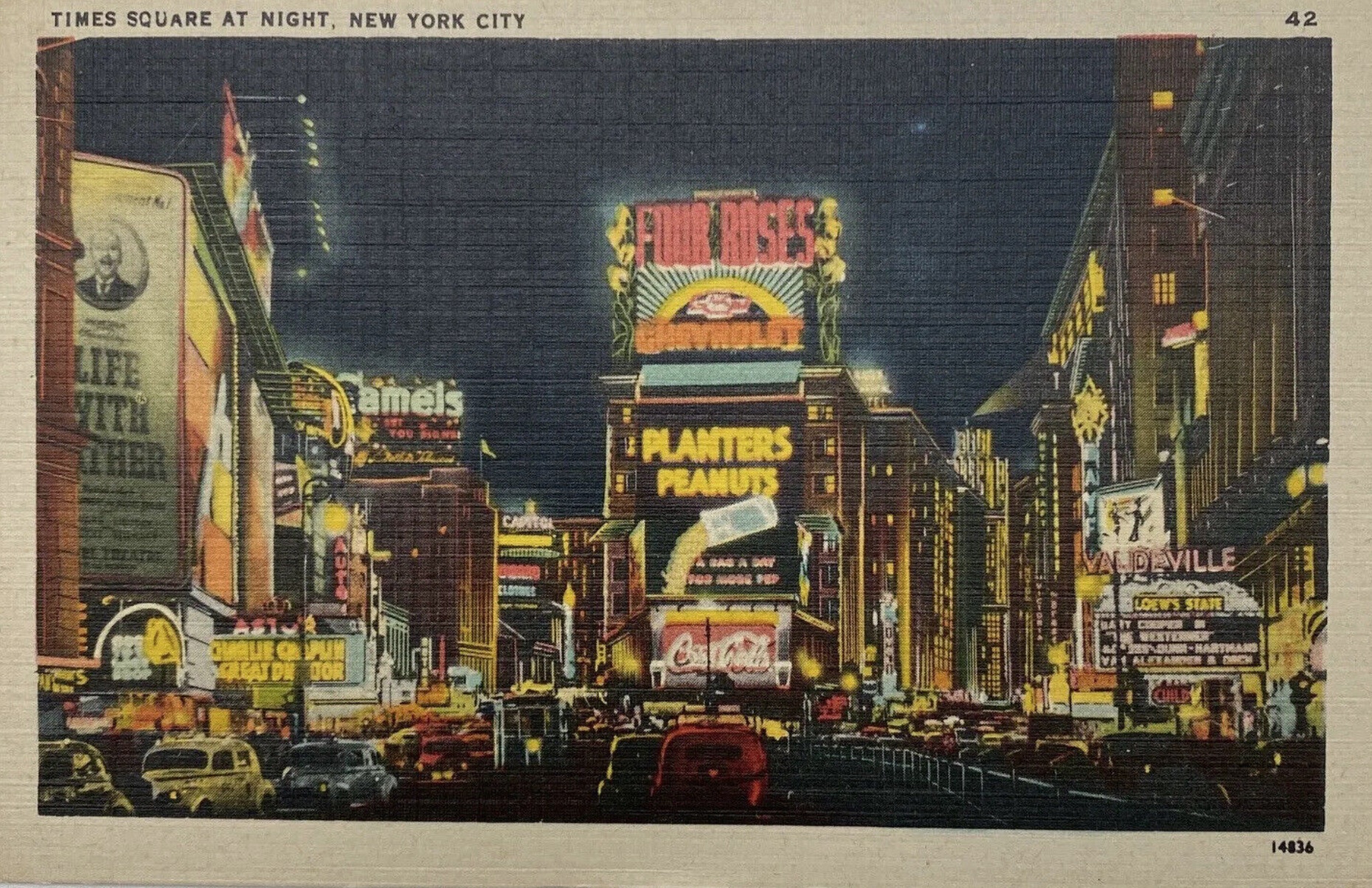

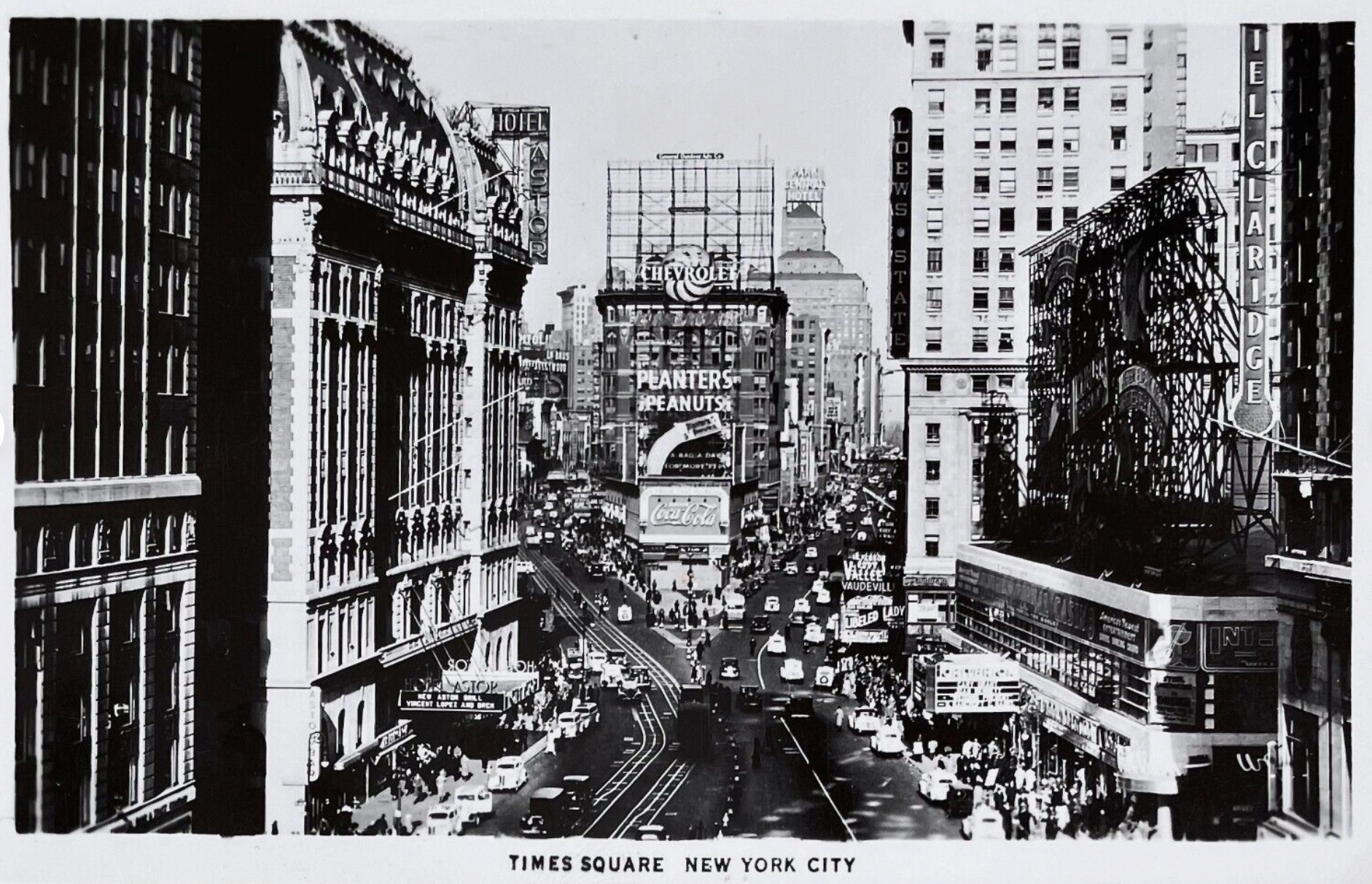

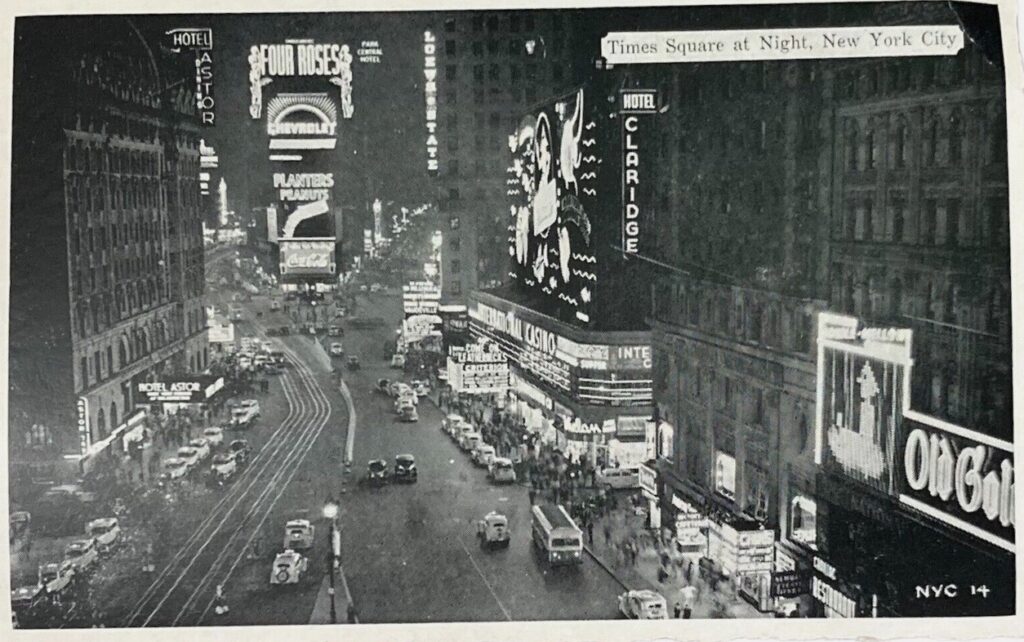

A few weeks ago, some random searching on eBay for American whiskey memorabilia led me to the purchase of an old postcard of Times Square at night with the Four Roses sign all lit up. It’s a black and white photo that had been colorized by hand to make it more vivid and I suppose modern [2]. There were actually many similar postcards of Times Square to choose from but I picked this particular one because it had actually been used and included a postmark which allowed me to date it.

That date shows the postcard was sent just 18 days after the Eisenstaedt photo was taken. I have to imagine that the events that led to the kissing photo (i.e. V-J Day) were still quite fresh in the minds of Betty and Charles, the people who selected and sent the card during their trip to New York City, as well as in the mind of their friend Jewell to whom they addressed it. Taken together this created a feeling of connection between myself, the card, people who sent it, the Eisenstaedt photo, and ultimately the Four Roses sign.

Dating the Photo

But seeing that postmark also got me wondering about the photo on the postcard itself. When had it been taken? There’s no way it could have been 1945 because the other signs in the postcard photo differ from what’s in the what’s in the Eisenstaedt photo [3]. The only things printed on postcard (aside from the title, name of the printer, and a suggestion on where to write your message) are two numbers: “14386” and “42.” The latter was clearly a printer’s catalog number of some sort but the other one, 42, might have been a year. Perhaps the photo been taken in 1942?

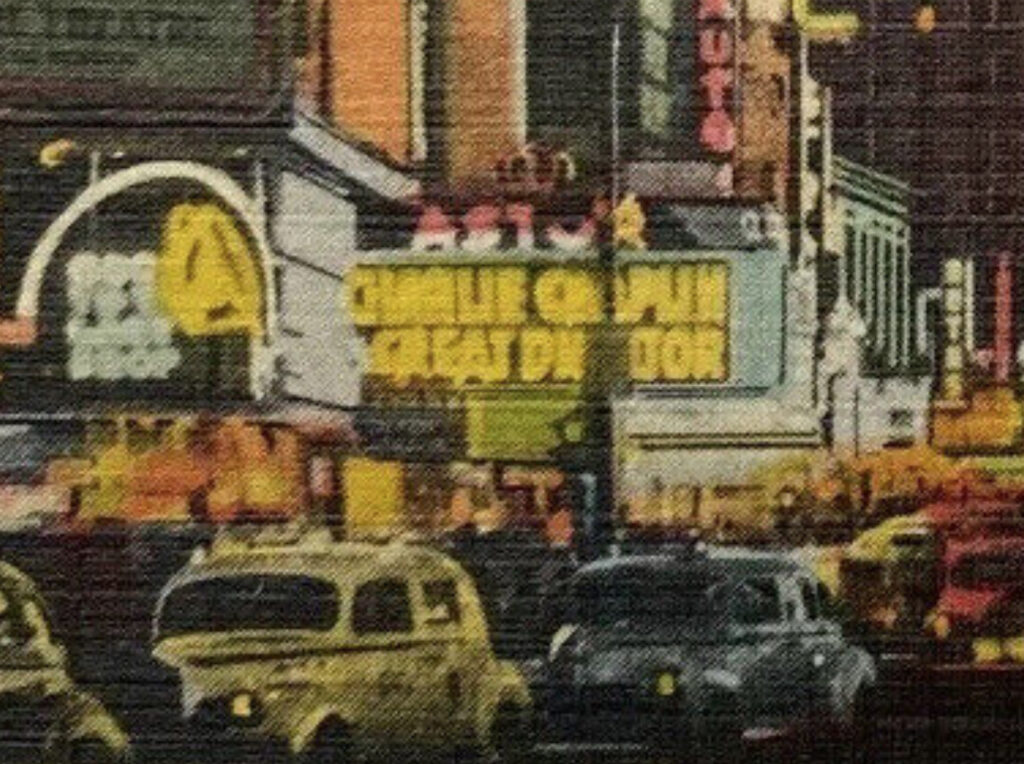

Then I had a further thought: the Times Square district, in addition to being home to live theater in New York City, was also a place where movies would premiere and play in their first run. And I could see the marquees of several movie theaters in the photo. If I could make out the titles of these movies perhaps I could better and more accurately date the photo. As it turned out, I could make out the titles of two films: The Great Dictator and The Westerner, both released in 1940.

Based on the release dates of these films, the picture on the postcard that Betty and Charles picked when they visited Times Square in September of 1945 had probably been taken five years earlier, in 1940. Now I write “probably” because one unknown here is how long films in those days would stay playing at the same theater—probably longer than they do today. It does however seem unlikely to me that both films, debuting in 1940, would have been popular enough to still be running two years later. So I think the 1940 date is safe. And that number “42” printed on the card, if it is a date, probably referred to the date of card’s printing.

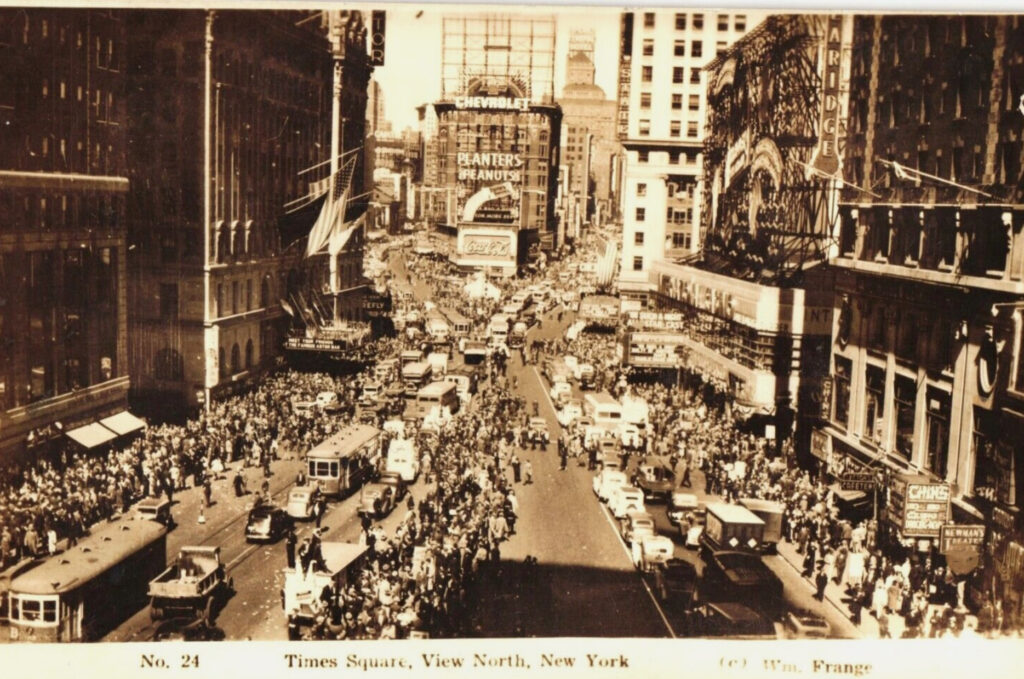

Having sorted all of this out I then started to wonder: exactly how long had the Four Roses sign been in Times Square when the 1940 photo was taken. Furthermore, when did the sign come down. I actually now had a means to determine these dates using the movie marquee trick. And as it turns out, not only have picture postcards of Times Square been printed for many many years it also seems that practically every photograph was taken from about the same vantage (likely the building at 1 Times Square at the south end) in which several movie theater marquees are visible [4][5]. I just needed to find postcards from a range of different times, before, during and after the sign had been there, then try to date them based on what movies were playing. Thanks to eBay, the same place I got the card Betty and Charles selected in 1945, that turned out to be rather easy.

The earliest postcards I was able to date show what Times Square looked like shortly after the repeal of Prohibition, based on the films Libeled Lady (1936) and Oh Such a Night (1937). The Four Roses sign is absent but you can see the place the sign would soon occupy [6]. The equally famous Chevrolet and the Planter’s Peanuts signs are present however [7].

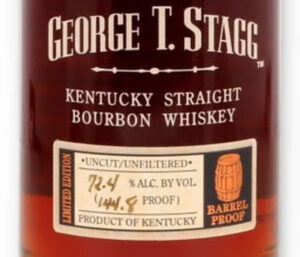

Before the end of 1937, based on the film The Last Train from Madrid, the sign finally makes its first appearance. Importantly this date settles the question of whether the sign had been put up by the Frankfort Distilling Company (what had been Paul Jones Jr. Distilling Company before Prohibition) or by Seagram after they purchased Frankfort in 1943. It would have been Frankfort which made the investment before Seagram owned the brand.

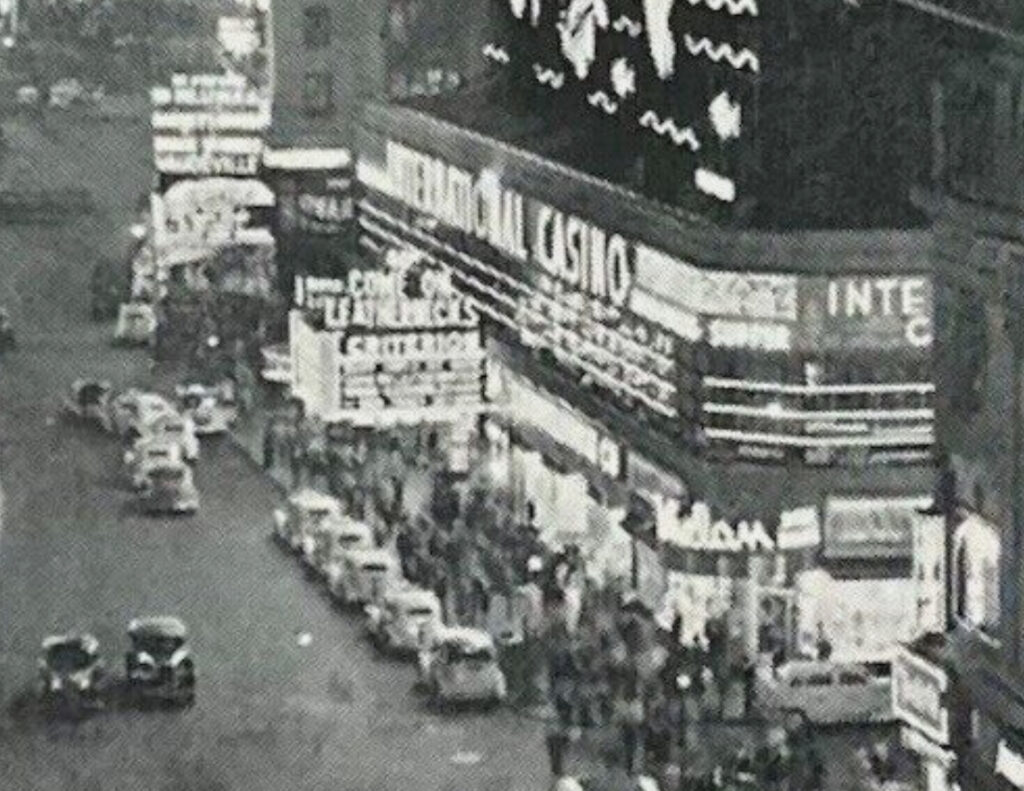

Though now we’ve established the year the sign went up, I am also going to include this postcard from the following year, 1938, dated by the film Come on Leathernecks!, just because this is a much better and striking photo of it than in the colorized one from 1937.

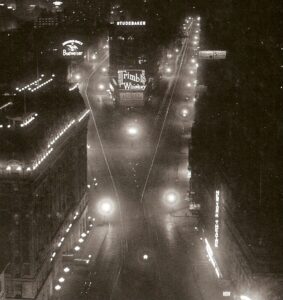

And here’s a much less famous photo on the same day as the 1945 Eisenstaedt photo. This would likely have been taken in the early evening after more people had come home from work and had time to assemble in Times Square en mass.

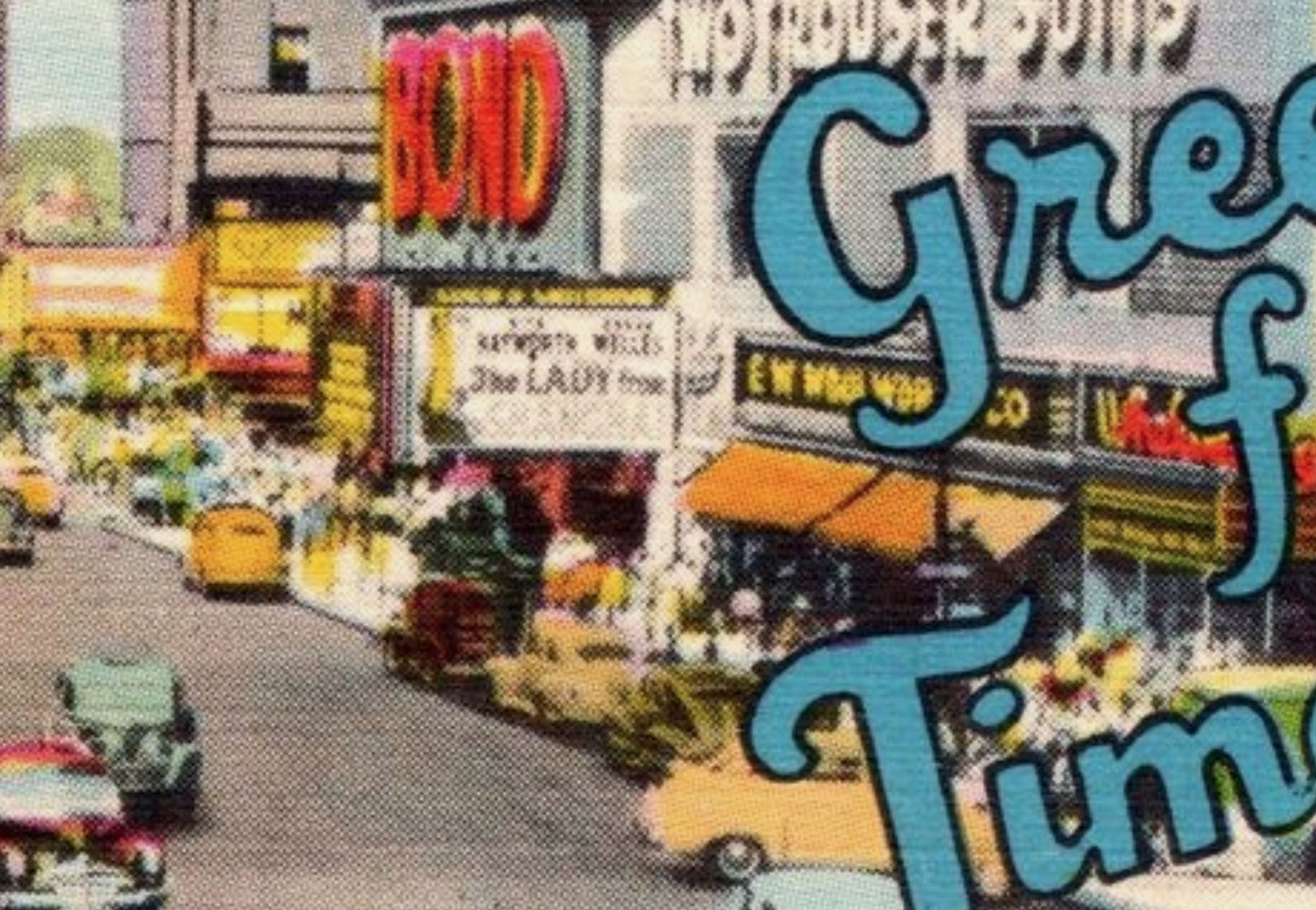

The sign’s tenure in Times Square would not prove in the end to be terribly long. In 1947, the year the film The Lady from Shanghai debuts, the sign had already been taken down. The Chevrolet sign (notably absent in 1945) now occupies the space making it the most prominent sign at the north end of Times Square [8]. This could have happened anytime after the Eisenstaedt photo was taken but I was unable to locate any picture postcards I could date to either 1945 or 1946.

So the Four Roses sign remained in Times Square for only eight years. It doesn’t seem terribly long when you think about it. But it does serve as an accurate reflection of brand’s strength coming out of Prohibition as well as the long slide down experienced by all American whiskey brands coming into the 1950s [9]. And somewhere in the middle of that journey it was captured, fittingly enough, in Eisenstaedt’s famous photo.

—

Notes:

[1] People frequently remark that they had never noticed the Four Roses sign in the Eisenstaedt photo when they see reproduced it in Young’s book. This is not surprising: the photo, when it appeared on the cover of Life, was cropped to better center its subjects. The Life magazine logo partially obscures it as well. Also, as an aside: in researching this article I learned that there are in fact a few different versions of the photo floating around. And Eisenstaedt was also not the only photographer to spot and document the couple. Navy photojournalist Victor Jorgensen also caught the kiss, albeit from a different and much less dramatic angle, and minus the Four Roses sign. Here’s a link to his much less famous photo as published by The New York Post.

[2] The choice of colors used for the Four Roses sign in that hand colored photo are sadly inaccurate. The letters should have been yellow (a color long associated with the brand) and the roses flanking them red. It’s unclear why the publisher chose to swap these colors but they did. According to Al Young’s book, the sign was also animated: it would start out dark (off) then the roses would “grow” from the bottom to the top of the sign at which point the letters “Four Roses” would light up from left to right. They would turn off to be replaced with the phrase “A Truly Great Whiskey!” and then animation would begin again. Here’s a very short clip of the sign in action, though it’s not very well framed.

(Take note of the movie marquee in the lower left of the frame: it’s The Great Dictator which dates this clip to 1940 or possibly 1941, depending on how long Chaplin’s film played at The Astor.)

[3] Based on other postcards I found, it seems ads changed fairly frequently over the years. In the Eisenstaedt photo, the ad below Four Roses is for Kinney blended whiskey; in the postcard postmarked 1945, the ad is for Chevrolet.

[4] I did find some very early photos of Times Square from before any movie theaters were located there. Until the 18090s it had been the center of New York’s horse and carriage trade. (And see Note #6, below.) But I didn’t need to go that far back in time: I knew the Four Roses sign couldn’t have been erected earlier than 1933, after Prohibition was repealed.

[5] The movie theaters I could identify by name were The Astor on the west side of the square (photo left) and The Paramount on the east (photo right). There were also two other theaters on the east side, a bit further uptown (north) one of which was Loew’s State Theater and the other The Criterion.

[6] This seems like as good a place as any to include something about the building behind the ads, the one to which they were attached. This was the Studebaker Building, erected in 1902. It stood there until 2004 when it was finally demolished. It was initially leased by the Studebaker Company which used it as both office and factory space for its carriage and then automobile businesses. Times Square, which had originally been associated with the carriage and horse trade in New York City, seemed like a natural place for Studebaker to call home. Studebaker operated from the building until 1910 when it moved out, partially in response to the development of the area as an entertainment district hosting theaters and restaurants. Below is a photo of the Studebaker Building in 2004. Wikipedia has more information on the building’s history.

[7] It’s worth noting that over the span of years Chevrolet and Planter’s Peanuts ads were put up and taken down more than once. The Chevrolet ad also eventually took the place of the Four Roses ad after it came down. See also Note #8 below.

[8] It’s notable that neither the Chevrolet or the Planter’s Peanut signs appear in the 1945 Eisenstaedt photo though both are clearly there in photos take before and after that year. The ads we do see, for Kinsey blended whiskey, Ruppert beer, and Pepsi (which replaced a Coke ad), must have only been up for a couple of years in the mid-1940s. Why this might have happened is a bit of an interesting mystery.

[9] I also have to wonder whether Seagram had the sign taken down as part of its general deprecation of the Four Roses brand, which, despite owning, saw as a competitor to its own ‘favorite sons’ Seagram’s 7 and Crown Royal.

![Read more about the article A Pilgrim in Shively [Part II]](https://americangrain.stream/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/IMG_2819_FourRoses_Warehouse01-300x225.jpg)

Excellent article. I love that period of American history. Thank you for your research.

Your essay is a great detective story I loved reading how you were able to create a timeline….Also searching on Ebay for bourbon memorabilia….