For the past few months I’ve been slowly working my way through Karl Raitz’ book Making Bourbon: A Geographical History of Distilling in Nineteenth-Century Kentucky (University of Kentucky Press, 2020). As books on Bourbon go, this is a particularly dense informational ‘confection’ that’s been well researched and annotated. So I haven’t minded taking my time reading it. I’ve learned a number of interesting things, taking my own notes.I figured it would be fun to share a few of his observations and my responses.

As you might expect from a ‘geographical history’ Raitz spends a lot of time at the start looking into how natural resources did and didn’t play a role in building Kentucky’s early reputation for making excellent whiskey. Those resources include fertile land for growing grain, grazing land for livestock, hardwood forests for fuel and barrel wood, and of course, a reliable supply of clean water. Raitz particularly emphasizes the significance of this last resource: abundant water is critical to making whiskey, not just for distilling itself, but for growing grain and as a power source for running grist and saw mills.

But when it comes to various magical qualities ascribed to ‘limestone filtered water’ as a singular explanation for the success of Bourbon in Kentucky, Raitz’ begs to differ, breaking for the moment from his character as ‘disciplined researcher,’ almost taking delight in these revelations. It would seem that it’s not that the water doesn’t matter, it just doesn’t matter as much as the folks marketing Kentucky Bourbon would like us to believe. Neighboring states have similar hydrology, not all of Kentucky sits over limestone, and not all limestone springs provide water that was particularly well suited for distilling, at least without some amount of pre-processing.

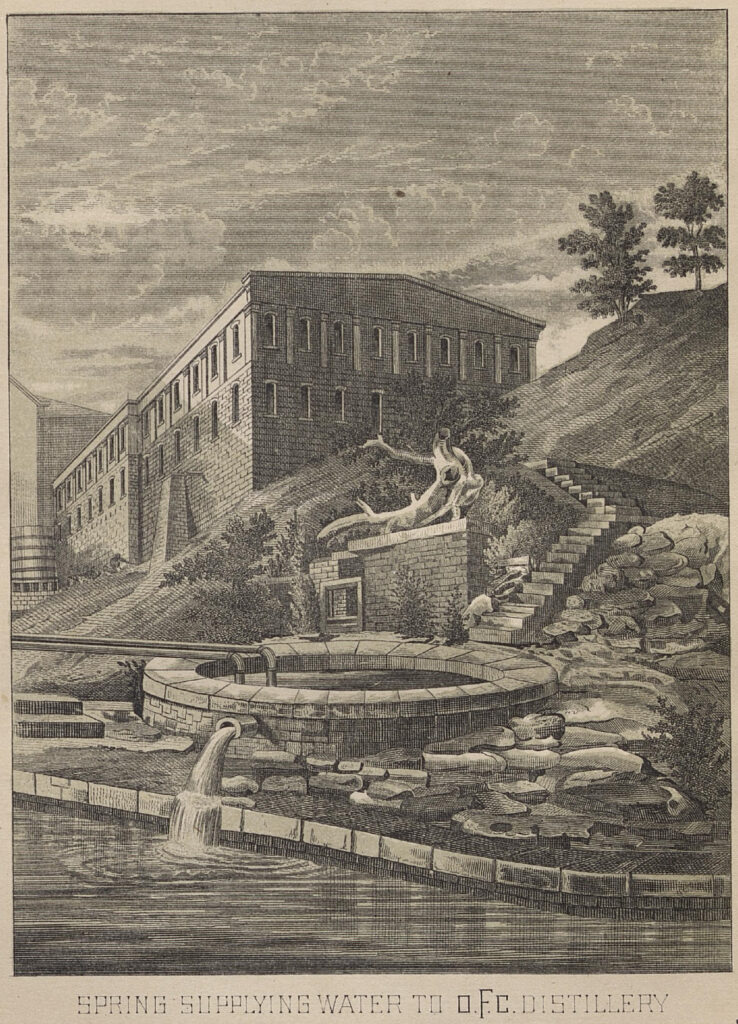

One particular case Raitz’ makes regards claims made by E.H. Taylor in the pamphlet he authored in 1886 extolling the various features and virtues of the O.F.C., Carlisle, and J.S. Taylor distilleries. On page 8 of the pamphlet, Taylor makes some bold claims for the water issuing forth from limestone cliffs adjacent to O.F.C.. A testament from “Professor Barnum, chemist of Louisville, Kentucky” makes, among other claims, that the water:

“…is of a wonderful purity, and of peculiar adeptness for the manufacture of whiskey.”

However Raitz also points out that while some of the water might have been coming from the miraculous spring, insurance maps from the same time show that the O.F.C. distillery was also drawing water directly from the Kentucky River using pumps and a pipe which appeared to be spliced directly into the one coming from the spring. So much for the myth of wonderful purity.

Pingback: The Missing Outage – In the American Grain